- Home

- Jennifer Shahade

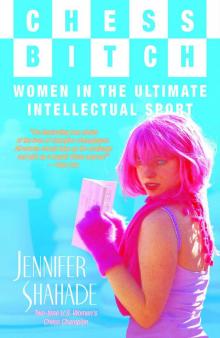

Chess Bitch: Women in the Ultimate Intellectual Sport Page 13

Chess Bitch: Women in the Ultimate Intellectual Sport Read online

Page 13

Midway through the event, I lost to Grandmaster Alexander Fishbein. I needed to get my mind off of chess, so I went to the Crocodile Cafe, a bar and concert venue. Upon entering, I was surprised to see another chessplayer, Grandmaster Larry Christiansen, with a beer and a steak, also unwinding from the tournament stress. I ordered a glass of wine and later went next door, where there was live music from local punk-rock bands.

The break was refreshing. Apparently Larry was also relaxed by his break. He went on to win the tournament. In the rest of the event I played with unprecedented confidence, earning draws against players I had previously been in awe of, such as Grandmasters Yasser Seirawan and John Federowicz. In the penultimate round, I played against a master originally from Armenia. After twenty moves, the position was equal, but I saw a chance to set a trap. I made a move that seemed like a blunder—he could win my Rook. He followed this variation, but missed the zinger I had at the end. A few moves later, he resigned.

I couldn’t get up for a few minutes after the game. I was sitting on my legs throughout the game, and now they were numb. I felt dizzy with happiness—I had clinched the U.S. Women’s title with a round to go. In the final round, I played against a grandmaster. If I won this game, I would place third and win a norm toward my grandmaster title. I ended up losing that game, playing very badly. One of my most brutally honest friends wondered if the reason I played so poorly was because, having already clinched the women’s title, I had relaxed. Perhaps if I were male, he suggested, I would have played harder, knowing that the only way to get attention at a U.S. Championship would be to prevail against the entire field. This comment reminded me of the reasons that the Polgars questioned women’s prizes and events. At the same time, I’m sure I would not have been on that high board in the last round if it hadn’t been for the women’s tournaments and prizes that encouraged me in my teens to stay with the game. Despite that last-round loss, the tournament was a big success for me. In interviews after the tournament I was asked if I liked the new format. I won. Of course I liked it.

I celebrated a lot. On the Saturday after the tournament, I went to an all-night warehouse party back in Brooklyn with Gabi, a dancer and artist whom I’ve been close friends with since high school. Proud of my victory, she was wearing a shirt that was meant to say “Jennifer Shahade is a man-eater” in gold marker, but the pen ran out of ink midway through, so it only read “Jennifer Shahade.” I was flattered nonetheless. At this party, no one played chess, but word spread through a few circles that I had just won the U.S. Women’s title—news that was greeted with congratulations combined with disbelief: first that chess was a professional sport, and second, that the blissed-out, blue-wigged girl was its new champion.

Often I am eager to promote the game and tell nonplayers all about my career, but other times I keep my status secret. I fear that the conversational dynamic will change into one of surprise, sometimes disbelief, followed by a litany of questions that can turn an equal exchange into an interrogation. To avoid this I either say, “I’m a teacher”—which is true—or I lie, claiming to be a circus performer. On the other hand, I can also be annoyed when I get no recognition as a specialist. One time when I was at a bar with Gabi, we met a charming man with lots to say about film and politics. When the bar closed at four, the conversation retired to my apartment. The topic of chess had not yet come up. Glancing around the room, the man noticed chess magazines and sets scattered around, and he began quizzing my roommate Eric on the game, assuming that the male of the house had to be the player. Eric, who is a strong amateur, noted my annoyance and tried to divert the questions to me, but the guy was not getting it. By this time the sun was coming up, and I, coming down, was ready to call it a Saturday night. This man, despite ignoring me on chess matters, was interested in me and wanted my phone number. I must have been bitter or just too tired to respond, so he left dejected, numberless. Gabi described the incident as painful to watch, while Eric said, “I felt so bad—I gave him my business card!”

Until Seattle, I had not realized how much never winning a national title had bothered me. The money was also important. Moving, books for college, and New York prices had strained my budget. I needed the $9,500 check, along with the pay increases, invitations, and exhibitions that followed the title. I was particularly excited about the U.S.-China chess summit, scheduled for Shanghai, China, in the summer of 2002. The Chinese women’s chess team was the best in the world, and I hoped that in Shanghai I might be able to understand why and how they were the best.

7

Chinese Style

Women hold up half the sky.

— Mao Zedong

Along the back streets of today’s Beijing, hidden from the hustle and bustle of bicycles and cars, dozens of men crowd around

dusty chessboards, playing xiangqi, or Chinese chess, in the open-air. Exploring Beijing on foot, I rarely encountered a girl or woman playing these casual games. A lay observer would have no way of knowing that it is young women who are the stars of board games in China. Chinese women have captured four consecutive Olympiad gold medals—1998, 2000, 2002, and 2004—and have produced two Women’s World Champions. The Chinese government has supported the promotion of chess, a trend that was accelerated by the success of Xie Jun, the trailblazer of women’s chess in China. Young players, many of whom were adept at xiangqi, were encouraged to switch to chess and enroll in the training center in Beijing, where they were able to develop their talents under the tutelage of experienced masters and coaches.

Xie Jun was born in 1970 in an army base outside Beijing, where her father was posted. Jun means soldier in Chinese, a reference to her father’s occupation, but the choice of Xie Jun’s name has a larger significance.1 “The name Jun is more often given to boys, but the year of my birth was in the midst of the cultural revolution. During this turbulent period in modern Chinese history, it was common to minimize the differences between men and women, and this was also reflected in the names given to newborns.” During the Cultural Revolution, launched in 1966 by Mao Zedong, Chinese culture was meant to be purged of the “Four Olds”: old ideas, habits, customs, and culture. At this time, traditional Chinese games such as Go, Mahjong, and xiangqi were banned. Books were burned, historical temples and sites were destroyed, and traditional gender roles eroded.

By the time Jun was a small child, the Cultural Revolution had ended, Mao had died (1976), and the ban on board games was lifted. She learned xiangqi at six years old and took to it immediately. Her father accompanied her to the streets, where she competed against middle-aged and older men. At eleven, Jun won Beijing’s girls’ championship in xiangqi. She was spotted by chess trainers, who taught her international chess and entered her in the Beijing team. Her passion for xiangqi transferred easily to Western chess. The skills required for excellence at both games are similar. Jun’s progress in chess was rapid. She became, at fourteen in 1984, the youngest Chinese national master. In 1988 her local team found a sponsor, which permitted her to travel to the World Junior Championships in Adelaide, Australia. She became more serious about chess after she tied for second place.

Xie Jun’s spectacular breakthrough came two years later, in the candidate cycles—a two-year series of tournaments to determine the challenger to Women’s World Champion Maya Chiburdanidze. In 1990 Xie Jun won a preliminary tournament in Malaysia, qualifying to participate in the candidates’ finals in Georgia. In the second round, Xie Jun won against local heroine Nona Gaprindashvili. Xie Jun’s compassionate nature is evident in her description of the encounter:

“I felt overcome by a feeling of sadness at this moment, when Nona realized that she had no more chances and I was about to mate her, I could see the tears in her eyes. Every time when Georgian players won a game, the three to five hundred spectators applauded enthusiastically. But now there was a dead silence in the hall. I could not feel as happy as one would normally expect. The whole situation had touched me and I felt too much sympathy for my opponent.”

Xie Jun won her last round game against Nana Ioseliani, catapulting her into a tie for first with Yugoslavian Alisa Maric. The two would play a match to determine who would face Chiburdanidze later that year. Xie Jun won the match, held in Yugoslavia, by two whole points. The chess world and the Chinese press were astonished: Xie Jun was the first Asian to compete for a World Championship in chess. She was just twenty years old.

To Chinese head coach Liu Wenzhe, Xie Jun’s qualification for the finals was a triumph of historical proportions. In The Chinese School of Chess, Wenzhe promises, “The Chinese school will be pre-eminent in the chess world. This is the necessary logic of chess history.” But such an upheaval would take time, and Xie Jun’s victory caught even the optimistic Wenzhe by surprise. In assessing Xie’s chances, Liu was reserved: “Taking into consideration Chiburdanidze’s skills and experience, as well as those of the Soviet coaches, the overall strength of the Soviet team is greater than ours. It will therefore be very difficult to win the match. Xie Jun has to undertake thorough preparation.”

All of China’s chess resources were poured into the upcoming match against Maya. Wenzhe summoned every grandmaster in China, all men at the time, to provide support for Xie Jun. Ye Jiangchuan, first board for the Chinese national team and a coach of Xie Jun, told me that the Chinese women play so well “because the men help them.” When I reminded him that men had also helped the women in the Soviet Union, he laughed and said, “Here, the men really help the women.” Each grandmaster was assigned a different set of openings to work on at home. They were to convey to Xie Jun their deep understanding of the positions along with detailed and original analysis. During this period Xie Jun’s days were tightly scheduled. Eight hours were devoted to chess, along with blocks of time set aside for light exercise and meals. (The transcripts of the training program are published in Wenzhe’s Chinese School of Chess.)

The chess confrontation between the Soviet Union and communist China coincided with a turbulent time in the USSR, which was crumbling as the match was played. Midway through, Xie Jun realized: “Maya was not at her best throughout the match. The timing coincided with huge changes in the former Soviet Union. In Georgia, civil war had broken out and I cannot imagine that Maya ever had a peaceful mind.” Indeed, Maya confirmed in interviews that, at the time, she was distracted by politics.2

Because Xie Jun had played in few international tournaments, she was something of a mystery. It was clear that she was young and talented, but her legendary Georgian opponent was higher rated and a big favorite. The match was held in Manila, Philippines, the first time a Women’s World Championship was held in Asia, and the crowd was naturally rooting for Xie Jun. In the first game Maya achieved a better position with black, but Xie Jun played resourcefully, finding a Knight sacrifice that led to a draw after a ten-move variation. The eventual triumph of youth over experience was underway. The second game was a quick draw. Maya made a mistake in the third game, and Xie Jun pounced, drawing the first blood of the match. Maya then came back to win two games in a row. A series of draws followed, until Xie

leveled the match with the black pieces in round eight.

Top: Xie Jun, Susan Polgar. Bottom: Nona Gaprindashvili, Florencio Campomanes, Maya Chiburdanidze.

Xie Jun gained momentum after her eighth-round victory and she won her next two games with white. Maya was unable to catch up, so Xie Jun won the match, a final score of 8.5-6.5.

Her upset victory created a stir in China, where Xie Jun became a major celebrity. “I was not sure where I was or who I was. Chaos had set in,” wrote Xie Jun. “It was impossible for me to plan anything—my life had become a whirl of excitement.” She was even elected as a member of the parliament in 1993. Though the post was mostly ceremonial, Xie Jun rejoiced in her new role as politician, which she “considered a great honor. It was a tremendous experience for me…and a nice break from chess.” Xie Jun also took some time off from chess to pursue her university degree in politics.

Xie’s political career was short-lived. Toward the end of 1993, she resumed her training regimen, preparing for her match in Monaco, where she would defend the title she had won two years before. Xie Jun considered being a world champion an enormous responsibility, so she worked hard to improve her chess understanding after her unexpected victory. She gained the grandmaster title and raised her rating to over 2500. Her opponent was Georgian Nana Ioseliani, who had won the right to challenge Xie Jun after winning in the controversial tiebreak against Susan Polgar. Ioseliani was mercilessly defeated by Xie Jun, in an overwhelming 8.5-2.5 victory. Her improved skills were evident as she defended her title. Describing the one-sided match, Xie Jun’s remarks were once again gracious and compassionate: “Luck was on my side in the first game…I felt in great shape and winning four out of the first five games was beyond my wildest dreams…for Nana it must have been horrible. …”

Xie Jun’s third title defense in 1995 was unsuccessful. She faced a determined Susan Polgar, who duly crushed her, forcing Xie to confront the first major setback of her chess career. The kind and sympathetic words Xie had once had for both Maya and Nana were gone, replaced by an angry diatribe. She complained about the poor conditions in Jaen, Spain: the food did not suit her and there were no decent translators for the Chinese delegation. A chief gripe was the unprofessional conduct of organizer Luis Rentero. Rentero sent both Susan and Xie Jun letters, which harshly scolded them for making quick draws, imposing unprecedented fines. Rentero wanted every game to be exciting, but the rules had already been establish and Xie and Polgar both found the fines disrespectful and distracting. Xie Jun claims she was unable to calm down afterward. She gave Polgar nominal credit for her play: “I cannot say that her victory was undeserved.” She continued, though, “The incident with the letter was unforgivable. All I can hope for is that one day I will have the opportunity to play another match against Zsuzsa [Susan], under different conditions.” These candid remarks reveal Xie’s fiercely competitive streak.

Xie Jun was determined to reclaim her title. During Christmas 1997, she played in a nine-player qualifying tournament held in Holland. The two top finishers would play a match to determine the challenger to Susan Polgar. Russian Alisa Galliamova won first place, and Xie Jun came in second. So that neither player gains an unfair advantage, most title matches are held in a neutral location or split between both home sites. Half of Xie-Galliamova was set for Jun’s native China, in the large city Shenyang, and half in Kazan, Alisa’s hometown. At the last minute, Kazan backed out and the entire match was switched to China. Galliamova did not accept these conditions, didn’t show up for the match, and Xie Jun won by forfeit. Susan Polgar, who was starting a family in New York, protested the rushed proceedings of the Polgar-Xie rematch, and refused to play. Galliamova was chosen as a replacement, and invited to play Xie Jun once again. This time the match was conducted as anticipated, half in Kazan and half in Shenyang.

The games were interesting and hard-fought, in my opinion the most interesting chess of any World Women’s Championship match thus far. Xie Jun prevailed in the end, winning five games to Alisa’s three. Jun’s victories ranged from a 29-move checkmating attack to a 94-move win in an endgame.

The match was the final Women’s Chess Championship held with the classical three-week-long format. Kirsan Ilyumzhinov, the president of FIDE since 1994, decided upon an entirely new system, which he thought would help to popularize chess. First of all, the time control, (a preset time limit for a player to complete her moves; if exceeded she will lose the game) was changed, so that the average game lasted about three or four hours instead of the standard five or six. The tournament format shifted to that of a knockout, in which sixty-four players play two-game elimination matches. Ties of 1-1 are broken by rapid matches. The field is whittled down, round by round, into 32, 16, 8, 4, 2 until there is a four-game final, at the end of which a champion is crowned. The grand prize was over $50,000. The new idea was certainly more exciting, and the large

starting field gave young players a chance for the first time. Detractors argued that the knockout format and quickened pace resulted in games of much lower quality than those played in classical format. A player who would have few chances in a regular candidate cycle could have a few good games and emerge as World Champion. Elisabeth Paehtz described the new knockout as “more like gambling in a casino than world championship chess.”

Xie Jun, the highest-rated and most experienced player in the first edition of the event, held in New Delhi in 2000, was able to win handily, even in the more random format. She outplayed her first five opponents calmly, meeting her young compatriot, Qin Kanying, in the final round. Xie Jun outplayed her with a win in the second game, and drew the others. The all-Chinese final was indicative of the dominant position of China in women’s chess at the start of the twenty-first century.

In the two decades after 1981, when Xie Jun first turned her attention from xiangqi to chess, the number of casual chessplayers in China soared from a few thousand to five million.3 From all over the vast country, talented young players were recruited to train at the National Chess Center in Beijing. China’s future female team was coming together. Zhu Chen was only seven when she began to play chess in a local club. Just four years later, in 1988, she traveled to Romania to play in the World Girls’ Under 12 Championship. She won first place, becoming the first Chinese chessplayer to win a gold medal in an international event. After this victory, Zhu Chen was summoned to the capital to train. Zhu Chen desperately missed her family and yearned to return home, but her parents implored her to suffer through the homesickness by throwing herself into her chess. She did just that. She describes being so tired after grueling eight-hour sessions that she would collapse into bed at night, going on to dream of chess variations.4

Chess Bitch: Women in the Ultimate Intellectual Sport

Chess Bitch: Women in the Ultimate Intellectual Sport