- Home

- Jennifer Shahade

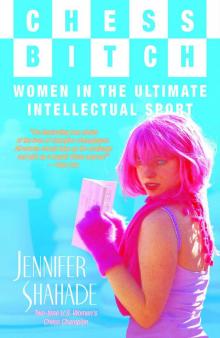

Chess Bitch: Women in the Ultimate Intellectual Sport

Chess Bitch: Women in the Ultimate Intellectual Sport Read online

CHESS BITCH

Women in the Ultimate Intellectual Sport

by Jennifer Shahade

Two-time U. S. Women’s Chess Champion

“One woman’s fascinating true story of the life of a champion chess player. All women should take up the challenge and pick up a board! Chess anyone?”

—Yoko Ono

“With crisp prose and a hypnotic rhythm, Shahade runs us through a vast range of colorful, affirming characters. Chess Bitch is a worldwide trot in search of a common humanity, a precise critique and a wild ride that transcends its own subject.”

—J.C. Hallman, author of The Chess Artist: Genius, Obsession, and the World’s Oldest Game

“She speaks playfully and provocatively on chess as meditation, as art and as philosophy …how passion can be more interesting than genius, and the importance of sexy.”

—The Philadelphia Independent

Copyright © 2005 by Jennifer Shahade

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

eBook ISBN: 978-1-890085-5-13

Cover design by Wade Lageose for Lageose Design

Cover photography by Gabrielle Revlock

Siles Press

www.silmanjamespress.com

Los Angeles, CA

Dedication

To my father Mike Shahade, for making me a chessplayer, my mother Sally Solomon for making me a writer, and in memory of my coach Victor frias, for making me a champion.

Contents

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Acknowledgements

Preface to eBook Edition

Playing Like A Girl

War-Torn Pioneers: Vera Menchik and Sonja Graf

Building a Dynasty: The Women of Georgia

Be Like Judit!

Bringing Up Grandmasters: The Polgar Sisters

Women Only!

Chinese Style

Juno and Genius

European Divas

Checkmate Around the World

Playing for America

Gender Play: Angela from Texas

Worst to First

Glossary

Appendix — Games

Notes

Bibliography

About the Author

Acknowledgements

This book would be impossible without the help of friends and family who advised and supported me at every phase. Two people in particular, my mother and Elizabeth Vicary exceeded all standards of generosity in every stage of the process. Without my mother’s stylistic advice, this would be a far inferior book. Many of the ideas discussed this book were developed and refined in conversations with Elizabeth.

Many thanks to Jeremy Silman, for sensing at the closing cocktail party of the 2003 U.S Championship that I had a book to write and convincing Gwen Feldman to take on this project. Thanks to Gwen for her advice, design work and taste. I am grateful to my editor Marjorie O’Hanlon for her thorough and thoughtful comments on the manuscript.

The following friends read various chapters and advised me along the way, saving me from many mistakes, and generally making Chess bitch a better book: Dr. Lewis Eisen, Chris Hallman, Paul Hoffman, Carrie Jones, Michael Le Grand, Jonathan Rowson and Greg Shahade.

Thanks to IM John Donaldson of the Mechanics Institute, Mark Ashland and Henk Chevret of the Hague Collection for sending me rare materials. Thanks to John also for suggesting to research Sonja Graf’s life. Thanks to Stephen Zeitz and Justin Phillips for supplying me with crucial materials on my visit to the John G.White collection in Cleveland, and to Nina Fried for collecting photographs.

Also thanks to Aarvind Aaron, Mig Greengard, Dirk Jan Ten Geuzendam, Jami Anson, Michael Klein, Rebecca Tuhus-Dubrow, Mike Nolan, Yelena Dembo, Ella Baron, Michael Negele, Gregory Braylovsky, Erin Fogg, Diego Garces, Gabrielle Revlock, Laszlo Nagy, Ron Young, Viktoria Johansson, Paul Truong, The Kasparov Chess Foundation and The American Foundation for Chess.

And to all the people mentioned in the book, for their candor and their time.

Preface to eBook Edition

The most frequent question I get about Chess Bitch is, “Why the title?” I explain that behavior seen as bitchy by a woman is often considered aggressive or assertive by a man. Of course, the catchy title also drums up interest for the book. There were some sour notes of censorship, like The New York Times refusing to publish the title in the tagline to an op-ed I wrote about popularizing chess. However, most mainstream venues from The Wall Street Journal to NPR embraced the controversial title.

I profiled and interviewed dozens of female chess champions for Chess Bitch. Now, nearly eight years after its initial publication, I’ve included some notable updates.

Judit Polgár is still the strongest female player in history, and now a mother of two.

Chinese, Georgian, Ukrainian, and Russian women continue to dominate Olympiads and World Championships, though the United States is also a force. U.S. teams won silver medals in the 2004 Olympiad in Mallorca (where I was a team member), as well as bronze in the 2008 Olympiad in Dresden.

Grandmaster and fashion model Alexandra Kosteniuk won her first Women’s World Championship title in 2008. Coining herself the “Chess Queen,” Kosteniuk has even copyrighted the phrase and goes by chessqueen on her popular YouTube and Twitter accounts.

Elizabeth Vicary, now Elizabeth Spiegel, starred in Brooklyn Castle, a highly acclaimed documentary about the I.S. 318 middle-school chess team she coaches, which has captured more National Championships than any other school in the country. The tagline of the movie is “Imagine a school where the cool kids are the chess team.”

Irina Krush continues to win U.S. women’s championship titles, having just captured her fifth at the time of this writing.

Just weeks ago, Mona May Karff was inducted into the U.S. Chess Hall of Fame and Nona Gaprindashvili entered the World Chess Hall of Fame.

Both Halls of Fame are housed in St. Louis, in a leafy, boutique-studded neighborhood called the Central West End. Across the street is the Saint Louis Chess Club, sandwiched between a trendy wine spot and a sports bar. Video art and grandmaster blitz games are displayed on dozens of flat screen monitors, while premiere chess events like the U.S. Chess Championships are hosted. The founders of the club and the Halls of Fame, Rex and Jeanne Sinquefield, are successful entrepreneurs and philanthropists. Widely considered the nicest chess club in America, the Saint Louis club is the centerpiece of what I judge to be the strongest American chess environment in my lifetime.

Chess apps on smartphones and the prevalence of “geek chic” have also promoted the game’s image, and chess.com has over seven million members.

Many of my own projects since Chess Bitch also broaden the appeal of our game. I edit the official website for the U.S. Chess Federation, Chess Life Online, where I post videos and edit blogs and tournaments reports. One of my goals is to make chess more glamorous and appealing.

I created a series of game related art projects such as Hula Chess, which was featured in galleries and museums, including the Guggenheim. With Daniel Meyrom and my dancer friend Gabrielle Revlock, we made a video installation merging chess and hula-hooping. The contrast between circles of hooping and the linear movements of chess are referenced in the finale, a potential perpetual check derived from a game by artist and chessmaster Marcel Duchamp.

In the even more provocative, Naked Chess, I reversed the famous photo of Ma

rcel Duchamp playing against a naked woman. The resulting video was a promotion for Marcel Duchamp: The Art of Chess, a book I co-authored. Following up on this, I played a simultaneous exhibition in Amsterdam against three naked opponents, a twist on the familiar chess exhibition in which a master walks in circles, checkmating dozens of opponents at once.

My prequel to Chess Bitch, Play Like a Girl: Tactics by 9 Queens is filled with tactical combinations and checkmates, all by female players. The first book of its kind, I hoped it would inspire young girls to stick with the game. I remember how important it was to me to play through Judit Polgar’s brilliancies, and imagine it was me delivering her beautiful queen sacrifices. The book was a project for 9 Queens, a non-profit I co-founded to promote chess to young people and women.

In the first few pages of Chess Bitch, I write that I don’t relate to gambling. And yet in 2006, my brother taught me poker and I was immediately drawn to the game. In the last few years, I became increasingly involved in the subculture. The lifestyle and the analytical approach required to succeed reminded me much of my first love, chess. I have played in poker tournaments all over the World, from Monaco to the Bahamas and also in thousands of online tournaments, where unveiling aggression is particularly easy for me. I’ve gotten a chance to watch the same sorts of gender issues play out with 52 cards just as I did in my teens and early 20s with chess. Many of the sexist tendencies I noted in Chess Bitch are even more extreme in the poker world.

I host my video art projects on the site Poker Fairytale, and I’ve joined a quartet of female poker players, The Grindettes, to help encourage more women to enter another male-dominated sphere.

Recently, I was unsure about my next career step, and my friends used my first book to remind me that I was a born risk-taker. I’m grateful that the world of chess armed me with the work ethic to attack other worlds fearlessly and with vigor. More than ever, I believe chess develops confidence and passion, the core of what “Chess Bitch” means to me.

May 2013

1

Playing Like A Girl

I am a woman who plays a man’s game, so I balance feminine emotions with masculine logic to become the strongest player possible.

— Zhu Chen, eighth Women’s World Champion

I was angry, overwrought, and couldn’t control my aggression and desire to win at any cost. It was the first time I had felt such intense killer instincts, and when I went to the bathroom to splash water on my face, I looked in the mirror and wondered, Is this what it means to play like a man?

It was Christmas in Las Vegas. Accompanied by my father, Michael, a now-inactive chessmaster, I was there playing in a chess tournament. As we walked through the hotel, the Paris Las Vegas, with its wide-carpeted boulevards, sky-painted ceilings, and beret-wearing waiters with fake French accents, my cheerful father ironically declared in a booming voice, “This is so authentic!” I was less enthusiastic. I don’t like gambling, unlike my father (who plays poker and blackjack), and I was baffled by the slot machine junkies and sad-eyed big-money losers. The hectic tournament schedule was set at two games a day. Each game would likely last between three to six hours. I was already exhausted and running on caffeine, sandwiches bolted in transit, and the adrenaline rush that accompanies an encounter as intense as a chess game.

The games were played far from Paris, in a sterile ballroom in Bally’s. I’d had a lukewarm tournament so far, winning two games against masters I was favored to beat, and losing two to grandmasters (the highest title in chess, other than that of world champion). My last-round opponent was a doughy, affable, completely inoffensive master. I wasn’t playing for any prize, so the source of my aggression was not lust for cash. Maybe it was the sharp attacking position that aroused my killer instinct. In any case, I was angry and playing like a man—or playing violently, which—for me—were the same. I was also playing badly: too many aggressive, but ineffective, moves. I sacrificed a Queen in a position where I saw that my opponent’s best response—rejecting my Queen sacrifice and fortifying his own position—would lead to a winning game for him. With just one minute on my clock, I was going to lose! My opponent offered me a draw. Riled up with all that masculine fire, I had the nerve to decline. With the next move, I came to my senses and renewed the draw offer: luckily my opponent, who by now had a clear advantage on the board, shook my hand in agreement. Did his lack of ruthless courage mean that he was playing like a girl?

It was time for me to find out what “playing like a man” meant. From open-air chess parks to professional tournament halls, “playing like a girl” has negative connotations, while “playing like a man” is a standard to be admired and emulated. It is no surprise that “playing like a boy” or “playing like a woman” are rarer phrases. Men and girls are on opposite ends of a continuum of strength and power. Boys and women, in between, are less-apt categories for generalizing skill level.

I decided to start by asking women chessplayers if there were any feminine qualities that contributed to their chess skill. Former European women’s champion Almira Skripchenko responded after a pause. “I don’t know. No one has ever asked me that before,” admitting that, to her, “The male standard is the highest standard.” Many women named advantages in being a chess-world minority: “I receive more invitations and recognition as a woman” or “Some men play badly against women.” Biology is often used to explain the supposed inferiority of women in chess, but the women I asked only named advantages peripherally related to being female.

At the moment of writing, the rate of female chess participation, especially at the adult level, is astonishingly low. In the United States, fewer than three percent of competitive adult-rated players are women, a number that has remained constant for the past five years. In the worldwide ranking system of FIDE (Federation International Des Eches) the situation is slightly more balanced. There, about six percent of active adult players are female.

Interpreting the data in such a male-dominated group is complex, but a good place to start is with Elo ratings, named after Professor Arpad Elo. In the 1960s, Elo developed the rating system now used by FIDE to estimate the relative strength of chessplayers based on previous results. After each tournament, ratings are revised to reflect a player’s performance. A master player’s rating ranges from 2200 to 2400, and an international master or a grandmaster is usually rated between 2401 up to 2851, the highest rating of all time earned by Garry Kasparov in July 1999.

The percentage of top female players is similar to the percentage of active female chessplayers. For instance, there is one woman, Judit Polgar, in the top twenty players in the world and about four or five women in the top one hundred players in America. So there is little evidence that women play worse than men. There are, however, clearly fewer women who play. It is typical to confuse the low rate of participation with poor performance, so much of the rhetoric on gender and chess assumes that women are weaker players.

Explanations abound as to why women are rarely drawn to competitive chess, including Freudian theories, studies on the importance of testosterone, and evolutionary theories. Garry Kasparov, who held the World Champion title from 1980 till 2000, thinks that the ability to concentrate is the most important quality in measuring chess talent, and argues that women are more easily distracted: “A women’s train of thought can be broken more easily by extraneous events, such as a baby crying upstairs.” Kasparov believes that women are more sensitive to external stimuli, so that even a childless woman has maternal impulses that make it harder for her to focus. To test Garry’s theory, I propose that a tournament with one hundred female and one hundred male participants be held underneath a baby nursery. It would then be possible to see how men and women react and adapt their play to the distracting cries of babies.

American Grandmaster Reuben Fine, Freudian psychologist and World Championship contender, links the desire to play chess with latent, unspeakable desires. In his 1956 treatise Psychoanalytic Observations on Chess and Chess Masters,

Fine writes, “The unconscious motive actuating the players is not the mere love of pugnacity but the grimmer one of father-murder.” Women are less inclined to pick up the game, argues Fine, since they lack a “subconscious urge to kill their father(s).” Fine believes that the King attracts boys to the game because the piece is important (if it is trapped, the game is over), yet impotent (it can only move one square at a time.) He argues that adolescent males are in a similar state, because they are unable to express their budding social and sexual powers. In his view, the rules of chess mirror for boys the rules of sex. “Don’t touch your piece until you’re ready to move it” encodes to “Don’t masturbate.”

This outrageous Oedipal model is just one of many possible ways to decode the symbolism of chess. Fine’s theory of chess, admittedly provocative, is contrived and hard to apply. I prefer to think of chess in the spirit of Carl Jung, as a system of opposites, from the black and white colors of the pieces and squares to knowing when it is time to attack and when to defend.

A good chessplayer also strives to balance overconfidence and fear, practice and rest, and—in the game itself—tactical and strategic thinking. Tactics are short operations that force checkmate or a quick win of material (pieces or pawns) and require proficiency in calculating. When a good player calculates, she considers her possible moves, taking into account her opponent’s possible responses, and how she would play against each, and so on, until she is reasonably satisfied with her choice. Though many nonplayers and amateurs are fascinated by how many moves ahead a chessmaster can see, it can sometimes be easy to see twelve moves ahead if there are few pieces on the board, but extremely difficult to see three moves ahead if the opponent has a variety of responses, which lead to a dense web of variations. Strategic thinking requires long-term planning and maneuvering: when there are no tactics to watch out for or employ, masters play moves based on their intuition and experience, waiting for the time when the position will enable them to find more concrete answers. Even the very best players have difficulty with the tension, as Russian-American Grandmaster Gregory Kaidanov said to me: “I can play well tactically, I can play well strategically, but I have difficulty switching quickly between one mode of thinking to the other.”

Chess Bitch: Women in the Ultimate Intellectual Sport

Chess Bitch: Women in the Ultimate Intellectual Sport