- Home

- Jennifer Shahade

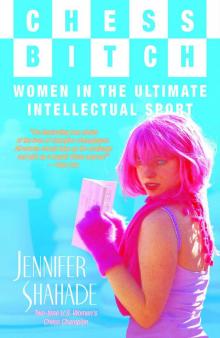

Chess Bitch: Women in the Ultimate Intellectual Sport Page 2

Chess Bitch: Women in the Ultimate Intellectual Sport Read online

Page 2

During a tournament game, balancing intense concentration with relaxation is crucial, to save energy for critical moments. Many players get up between moves to pace, eat an energy bar, or glance at friends’ games. It is easy to go too far with this practice, slip into daydreams, and totally lose concentration—and the game. Some men claim that thinking about sex diverts their focus. A twenty-two-year-old male amateur told me jokingly, “I would be a grandmaster if only I could stop thinking about sex during the game for more than fifteen minutes. I think it would be easier if I were a woman.” According to the 2003 American Champion, Alexander Shabalov, professionals have not overcome that obstacle: he said that most men, regardless of their strength, are thinking about sex for most of the game. With characteristic candor, the Latvian-born grandmaster tells me, “In most games, I am thinking about girls for about fifty to seventy-five percent of the time, another fifteen percent goes to time management, and with what’s left over I am calculating.” When I mention that twenty-five percentage points is a big range, Alexander agrees. “You can tell if it’s closer to fifty or seventy-five percent by the quality of the game. Fifty percent is great chess, seventy-five percent I can play okay, but where it is really dangerous is when it slips up to ninety percent.”

Learning the rules of chess takes a few hours, but gaining competence in its intricacies and developing a personal style takes years of work. Playing a highly focused board game for four to six hours is difficult, and neither men nor women are born with the concentration and motivation to excel at it. For that reason, I find the emphasis on women’s biological inferiority absurd: when it comes to chess, we are all born inept.

The desire to find gender-based stylistic differences is based on a belief that if women and men are different, they ought to play chess differently as well. Indeed, women and men do tend to have different chess careers and get started in the game for different reasons. In my usage, the category of women’s chess does not refer to some intrinsically female way of playing chess but rather to being a minority in the chess world, which can affect the way a woman plays.

The development of my own style was affected by being one of the few girls in chess. My brother, Greg, and father, Michael, were both masters by the time I became serious about chess, in high school. My father has a sedate style. He is an excellent calculator, but his tendency to choose solid, positional set-ups, such as the English opening (starting the game with the c-pawn, commonly thought as the safest first-move option), surprises some people in the chess world. English Grandmaster Tony Miles, after taking in Michael’s iron-man physique, loud voice, and commanding presence, said, “I thought you would play more like a thug!” My brother has a balanced style, which favors tactics but is also flexible. He does employ solid systems against opponents when he thinks they will be uncomfortable with long strategic battles. Impressed by Greg’s psychological awareness, one master told me, “Greg has the most pragmatic style I’ve ever seen.”

Michael, Jennifer, and Greg Shahade. (Photo by Sylvia Plachy.)

As a teenager, I played the most dynamic openings in the family, and tended to win by executing ruthless attacks. I improved rapidly between the ages of fourteen and sixteen. Just before I turned sixteen in 1996, I entered the Insanity Tournament, an all-night chess marathon that began at nine at night and ended at nine the next morning. I won the tournament and also gained enough rating points to join my brother and father as national masters. I was euphoric. My father, who had ridden on the train with me to the tournament and stayed to watch my games, joked gleefully on the ride home, “No one could ever say you play like a girl.” At the time, I considered it a compliment. I didn’t see any reason for my violent style except that I liked attacking chess. However, I was aware of the stereotype that women were more patient and passive when men were supposedly braver, and I wanted to be a hero too. In retrospect, I see my chess style was loaded with meaning—to be aggressive was to renounce any stereotype of my play based on my gender. I was also emulating the attacking style of the top woman player in the world, Hungarian Judit Polgar.

For a while, I played recklessly, and at first I lost many games because of my one-dimensional style. Many opponents altered their strategies when playing against me, choosing quiet systems—such as the English opening—in order to derail the tactical melees at which I excelled. This resulted in my progress pursuing a zigzag course: I dipped below master, and back up again, and then under again. I realized that I needed to learn other aspects of the game, so I began to study strategy manuals and endgame theory to improve my standard of play.

I abandoned my absurd desire to subvert stereotypes by playing violently. By the time I was nineteen, I started to mingle in the higher ranks of international chess, playing in world championships and the biennial chess Olympiads. I realized that to play like a girl did not have the same meaning at the top as it did in parks and scholastic tournaments. It turned out that to play like a girl meant to play too aggressively! This was most vividly demonstrated to me when a Russian coach looked at some of my boldest games and said derisively, “I see women’s chess hasn’t changed. Women have no patience; they always want to attack immediately.”

Even women players sometimes join the chorus. German youth champion Elizabeth Paethz told me: “Women are mostly of the more aggressive category. They don’t want to sit for six hours, so they attack and try to get the game over with. Probably this is because men in the Stone Age had the more focused goal of hunting, while women had a variety of tasks.”

Grandmaster Susan Polgar also believes that women have difficulties in strategic thinking, although her reasoning is based on more recent history: “Women are rarely given the freedom to think abstractly. Men are often afforded the luxury of having their basic tasks, like laundry and cooking, taken care of. Women are usually compelled to focus on the details of life.” Susan concludes, “This is the root of why women are equal to men in tactics, but still lag behind men in strategy.”

Polgar and Paehtz attempt to explain aggressive female play by examining the nature of women, although Polgar leaves open the question of whether the division of labor according to gender is natural or cultural—without reference to the particular conditions of the contemporary chess world. A feature of the present standard of women’s chess is excessive aggression, a playing trait common for masters rated 2300-2500 Elo, the range in which professional women fall. Grandmasters tend to have more balanced styles. To determine whether women are more aggressive than men, one would have to compare the games of the top female players with the games of randomly selected male players rated 2300-2500.

In determining a feminine style, the conclusions are rarely based on statistical analyses of games. Playing like a girl, whether it is supposed to refer to passive or aggressive play, is usually intended as an insult. This devaluing of the feminine in chess dates back to the 1300s and the birth of modern chess rules.

The modern Queen is the most powerful piece on the chessboard, shuttling across ranks and files, checkmating lone Kings, and grabbing loose pieces on an open board. This was not always so.

In the Persian versions of the game, there was no Queen. The piece that stood by the King was the Ferz, or the adviser. Replacing this male counselor with the Queen, the female sexual partner of the King, occurred after Persian traders transported the game to Europe in approximately A.D. 1000. Chess historian H. J. R. Murray thinks that this change came about because of “the general symmetry of the arrangement of the pieces, which pointed to the pairing of the two central pieces.”

The Queen began as one of the weakest pieces on the board, only able to move one square diagonally, and her presence was not revered. In 1345, when the Queen could only inch along the diagonals, a medieval writer described her force: “[Her] move is aslant only because women are so greedy that they will take nothing except by rapine and injustice.”1 Diagonal lines were then seen as sinister and sneaky, in contrast to the honesty of straight lines. The connotation l

ingers in English phrases such as “crooks,” or “straight-up.” In Go, which originated in China, the pieces do not connect on the diagonals. In chess, blundering on diagonals has always been more common than on the straight lines of the ranks or files.

The old game was slower, since it was hard to deliver checkmate without the mighty Queen of today. Games were rarely recorded, and to quicken the pace, players often began the games with tabiyas, midgame starting positions.

Around 1500 the rules of chess underwent a sudden metamorphosis, and the Queen was given much greater powers. The Bishop acquired greater mobility at this time also. These changes made the play of chess quicker and set up a balance between strategy and tactics, or intuition and calculation, which makes the game tantalizing to this day. The alterations occurred during the time of Columbus’s voyages, Isabella’s reign, the spread of tobacco, and the invention of the printing press. No single individual is given credit for the changes; probably they were initiated as a result of collective experimentation, brought on by dissatisfaction with the old game. Chess literature spread the new rules, which were rapidly standardized. Chess with its radical new rules was at first called “The mad woman’s chess game.”

Emory Tate, one of America’s most entertaining and talented senior masters, humorously displayed his ambivalence toward powerful women as embodied by the Queen. Emory has a spectacular style, and at open tournaments he gives impromptu performances, his muscled body writhing as he shouts out the moves of his games. Emory reels off his accomplishments in rapid-fire diction, punctuated with vocabulary that is often profane. In one of these so-called post-mortems, I was among several dozen onlookers when Emory exclaimed, “And now I made a triple-force postal move—Bitch to g5!” The first part of this is nonsensical rhetorical flourish—there is no such thing as a triple-force postal move. As for calling the Queen a “bitch,” Emory knows she is central to his inspired checkmating attacks. The reception of the potent, sixteenth-century Queen also showed a negative association with female aggression. The new Queen was not described in a positive way as the super queen or power queen, but rather pathologized as the mad, crazy queen.

Women are too docile, claimed English Grandmaster Nigel Short, to enjoy the highest levels of chess competition. He said, “They just don’t have the killer instinct.” Reuben Fine was straightforward in defining chess as “quite obviously a play-substitute for war.” But is chess really so like war? In chess, both players begin with armies of precisely the same strength and use only their intellects to express their aggression; in this way, chess is antithetical to war. Women’s World Champion Susan Polgar said that when she was four years old, she pictured chess as a “fairy tale” because her father told her dramatic stories involving the King, the Queen, castles, and romance. If chess is a metaphor for war, it is not war as hell, but war where fairness, females, and rules matter above all.

The power of the Queen foreshadows the strength of the women champions in this book, but it also hints at something more sinister. Medieval historian Marilyn Yalom writes that the queen is an “ultimate female status, but one which is played out in life as in chess on a predominantly male playing field.” Empowered women are often called bitches, or mocked for their lack of femininity. Nearly every up-and-coming female in the history of women’s chess has had her femininity doubted, complimented not for being a strong woman but for “playing like a man.” Many great women players have been called Amazons, which means literally “without one breast.” It seems that female chessmasters being referred to as Amazons can be taken as praise for their warrior-like abilities. In reality, emphasizing the manly attributes of strong women players casts their successes in a deviant light—almost as if their efforts are a gender-bending circus act.

In February of 2003 I received a call from Susan Polgar, the eldest of the legendary Polgar trio from Hungary. She wanted to get together. I was excited, because Susan was one of my childhood heroines. Susan, along with her sisters Sofia and Judit, was a child prodigy, trained from infancy in chess tactics and strategies as most children are taught the alphabet. Susan is one of a handful of women to hold the overall grandmaster title and is a former world women’s champion. Born in Budapest, Susan has lived in New York since 1995, where she moved to be with her husband. She started a family and took a hiatus from competitive play. Susan, recently divorced, has renewed her professional ambitions.

Susan and I met in a bookstore in Manhattan, where I found her flipping through a cookbook. She greeted me warmly, but moved quickly onto business, telling me that she was distraught by the lowly status of chess in the United States. In Europe, chess is a respected sport. It occurred to Susan that the top women players in the United States, with some training, would be strong enough to compete with the best women’s Olympic teams in the world. She hoped that this would promote chess in the United States. Susan would come out of retirement in order to train the team and play board one (where the strongest players from each team face off) during the next Olympic games, set for Mallorca, Spain, in 2004.

The Dream Team: Jennifer Shahade, Irina Krush, Anna Zatonskih, Elina Kats, and Susan Polgar. (Photo by Paul Truong.)

Four months after our meeting, along with three other young women, I was invited for a one-week training session to be held at the Susan Polgar Chess Authority, a one-level community chess center and chess bookshop that Susan founded. The club is in Rego Park, deep in Queens where English is often a third language. It was to be the first of eight official training meetings for what team publicist Paul Truong termed The Dream Team.

Anna Zatonskih was the only non-New Yorker on the squad, so she stayed with me in my Brooklyn apartment. The twenty-five-year-old WGM (Woman Grandmaster) arrived at my place and shyly presented me with a box of chocolates from Ukraine, where Anna had been born and raised. Anna has a wide jawbone; silky, dark hair; and legs so long that she seems overwhelmed by her own stature. Anna was not yet fluent in English, so the first few hours between us were awkward, until we sat down at the chessboard set up in my living room. Anna quickly opened up and showed me one of her best games, giggling with childlike glee as she replayed the moves: “And now I sacrificed another exchange!”

The next morning Anna and I took the long subway ride to Rego Park for our first session. We were excited and nervous about training with the famous Susan Polgar. Anna and I were early, and we chatted awkwardly with Susan about her club and our upcoming tournaments as the other members arrived.

Irina Krush entered the club next, brown hair back in a ponytail, wearing a jean jacket, eating an apple. Irina became an international master at sixteen, and was the youngest player to win a U.S. championship as a fourteen-year-old. At the time of this session, Irina was enrolled as a full-time student at NYU, but her devotion to chess is constant. “For me every game of chess is a character test—such intense situations arise so rarely in real life.” Irina approaches life as she does chess, with a contagious intensity. Though chess is her first and deepest love, Irina cultivates what she calls “mini-passions,” such as ones for the French language and tennis.

Rusudan Goletiani, an energetic and rail-thin woman in her twenties, completed the squad. Rusudan is from the ex-Soviet Republic of Georgia, where the first great women’s chess tradition originated. In boring moments of endgame lectures, I sometimes stared at Rusa’s snazzy high-top sneakers and imagined her jumping over tall buildings. Rusudan’s buoyant presence belies a serious character. In 2000, Rusudan fled a grim economic situation in post-communist Georgia. Upon her arrival in the United States, she spent most of her time coaching chess to support herself—this also enabled her to send money back to friends and family in Georgia. Consequently, her chess activity abated, and she was the lowest-rated person on the team. However, by common consensus she may be the most talented player, often reeling off long variations (long strings of projected moves) and finding surprising ideas in analysis.

The training program was exhausting. Each day began at te

n in the morning and ran until seven at night: grandmaster guests came, taught, and left. Conversations and lectures were conducted in a swirl of English, Russian, and chess. We analyzed complex endgames, investigated the weaknesses in our play by showing our worst games, and played training games against each other. This grueling work was rewarding for me as a chessplayer, but as a twenty-two-year-old woman, I was dismayed by a sexist idea that was forwarded during the session.

Michael Khodarkovsky, a Russian trainer who has worked with Garry Kasparov, is a sturdy, balding man with piercing blue eyes and confident diction. Michael began his session with us by saying, “I know that feminism is popular in the United States, but in Russia we understood that women and men play differently.” Michael advised us: “With this in mind, you should never be ashamed to tell your trainers most intimate details…or when you may not be able to play one hundred percent.” Paul Truong, a fuzzy-haired Vietnamese ball of energy with a tittering laugh, clarified Michael’s statement for the team: “Does everyone know what Michael is talking about?…Menstruation!”

I thought I had entered the twilight zone, an impression that was furthered when Susan Polgar, one of my childhood heroines, joined forces with Michael: “Now, menstruation may not require that someone take a day off, but it might affect, for instance, the choice of opening.” Michael mentioned a computer program that a Soviet friend of his had developed, which would determine how, at any given day, the menstrual cycle would affect play. I was too shocked to say much, though later that afternoon, I could not resist joking—after suggesting a poor move in analysis—that “It’s that time of month; can’t think straight.” The laughter that ensued made me hopeful that no one took the issue too seriously.

Chess Bitch: Women in the Ultimate Intellectual Sport

Chess Bitch: Women in the Ultimate Intellectual Sport