- Home

- Jennifer Shahade

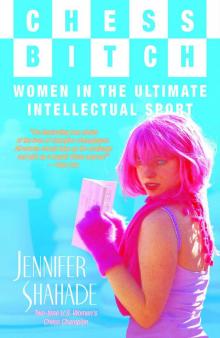

Chess Bitch: Women in the Ultimate Intellectual Sport Page 9

Chess Bitch: Women in the Ultimate Intellectual Sport Read online

Page 9

Defending himself against the many critics who have accused Laszlo of robbing his daughters of normal lives, he says, “They did have a real childhood, because they are not building sand castles, but real castles, castles of knowledge.”4 When questioned about her structured upbringing, Susan answers with a balanced view. “My sisters and I traveled to forty countries and had the chance to see things that most children could only read about in National Geographic. On the other hand, we missed out on doing some of the typical things that young people do, like going to the movies or hanging out with friends.” When I ask Susan what she regrets missing in particular, she seems at first to have trouble finding the words, then simply replies, “Goofing off!”

Susan’s battles were not with her parents. From a very young age she had disagreements with the Hungarian Chess Federation, which thought that she should play in the Hungarian Women’s Championship in order to prove herself as a top woman player. Susan refused, worried that playing against weaker opposition would be a waste of time and an impediment to her progress. She thought that the only way to earn her own grandmaster title was a steady diet of male grandmaster opponents. As punishment, she was barred from playing in tournaments in the West for the three years between 1982-85. Susan complained that this “crippled my career at a time when I had peak interest.”

When the ban on traveling was finally lifted, Susan and Sofia went to the United States with their mother, Klara, to play in the 1985 New York Open. From the start Susan fell in love with the city: “I used to sit on the subway and marvel that each person was a different color. That kind of diversity was unheard of in Communist Hungary. I knew I really wanted to live in New York City.” Susan’s wanderlust, evident from her first trips to London and New York, combined with her rocky history with the Hungarian authorities, foreshadowed the move that would come a decade later.

Even more painful for Susan than the ban on traveling was the ratings fiasco of 1986. FIDE made a controversial decision to increase the ratings of all female players by 100 points. The thinking behind this strange move was that the ratings of women were kept artificially low since they played only amongst themselves. Adding the rating points was thought to be an appropriate countermeasure. Since Susan, at this point, played exclusively against men, FIDE refused to add the points to her rating, making her the only woman who did not reap the benefits of the bonus points. As a result, Susan lost her first-place ranking among women: Maya Chiburdanidze leap-frogged over her. Susan told me, “I was heartbroken. My parents always taught me that in chess, if I study and work harder than my opponents, I would beat them. It felt like good results were not enough anymore. I got really depressed.”

While Susan was fighting the chess bureaucracy, younger sisters Sofia and Judit were being intensively trained to follow in her footsteps. In 1986 when Susan returned to play in the New York Open, her younger sisters accompanied her. Their results were incredible. Ten-year-old Judit won the unrated section with 7.5/8, while Sofia tied for first in a reserve section. In the following year they returned to New York, where both Sofia and Judit defeated their first grandmasters. Judit’s strength was particularly impressive, drawing glowing praise from the British daily The Guardian: “She is the best eleven-year-old of either sex in the entire history of chess.”

The threesome was a sensation. Here were three sisters who were possibly the strongest women players in the world. The Hungarian public and the chess world wanted the Polgars to prove themselves against the mighty Soviets, who until then had been resting on their laurels, unchallenged as the top women players.

The Polgars abandoned their usual refusal to compete in women’s events by accepting an invitation to play in the 1988 Olympiad in Thessaloniki, an old port city in Greece, enclosed on one side by the sea and on the other by mountains. American Grandmaster Larry Christiansen describes rough conditions in Thessaloniki: “The traffic noise outside our hotel extended to the early hours. The playing hall was utterly smoke-filled and the restrooms were primitive. Pollution was bad.” Still, Larry says the players had a great time, at after-game parties concentrated in a bustling hotel in the downtown. The Polgars did not socialize at all, devoting their free days and evenings to preparation. I asked Susan if her father forbade his daughters from going to the big dance held before a free day. “It was not recommended,” she said.

The Hungarian team was composed of Susan, nineteen; Judit, twelve; Sofia, fourteen; and Idliko Madl, eighteen, another promising junior player. The Olympiad competition is structured according to the Swiss system, in which teams are paired in the first round based on ratings. If there are ten players, the first-ranked would play the sixth-ranked, the second would play the seventh-ranked, and so on. Starting from the second round, teams with the same scores play one another.

Top teams such as the Soviets and the Hungarians tend to be paired near the middle of the tournament. This time they were paired together in the fifth round, dubbed by the tournament bulletins as “The Clash of the Amazons.” In the three games of the round, Judit and Susan both drew and Madl won (Sofia sat out), giving Hungary a crucial 2-1 victory over the Soviets. But it wasn’t over. Teams can only play each other one time, meaning that the winner of the entire event hinged on which team routed their opposition more harshly in the final rounds.

Twelve-year-old Judit finished with 12.5 points out of 13, the half coming from her draw in the Soviet match. The way she won her games was just as memorable as her awesome score. Her quick seventeen-move victory against the Bulgarian player, Pavlina Angelova, introduced the world to Judit’s inspired style, which featured graceful development, a subtle Bishop sacrifice, followed by a Queen sacrifice that forced her opponent’s King into an inescapable trap. The game was over: it was checkmate. Judit’s style was already becoming legendary. Just winning was not enough for her—she had to tear her opponents to pieces.

It was this tournament in which Elena Akmilovskaya made her sudden unannounced departure to marry John Donaldson, paving the way for a Hungarian triumph. The young squad composed of teenagers and preteens broke Soviet dominance of women’s Olympiads, which dated back to the inception of the events in 1957. “We were euphoric,” says Susan.

The chess world was impressed, while the Hungarian press hailed the Polgars as national heroines. Susan recalls how “the victory changed our lives completely.” Judit said, “Everybody now wants to help us who before were against us.” Judit sarcastically mocks these fair-weather friends. “Oh, yes, you are very nice.”5

Two years later the Polgars attended the 1990 Olympiad in Novi Sad, Yugoslavia, hoping to repeat their gold-medal performances. This time the three Polgars played on the top three boards: Susan, first; Judit, second; and Sofia, third; with Idliko Madl as the reserve player. The Polgars had improved in the past two years, but so had the Soviet squad. Women’s World Champion Chiburdanidze was joined by former champion Nona Gaprindihasvilli along with two younger players, Russian Alisa Galliamova and Georgian Ketevan Arakhamia. The crucial match between Hungary and the Soviets did not go well for the Polgars—Judit and Sofia both lost, while Susan managed to narrow the margin to 2-1 by defeating Chiburdanidze on the first board.

The final rounds decided the contest, just as they had in Thessaloniki. This time the Soviet and Hungarian teams had accumulated the same number of points. The gold medals would have to be determined by the first tiebreak, the strength of their respective fields, which would be judged by adding up and comparing the results of all the teams Russia and Hungary had played throughout the event. The Polgars won by a hair. The medal for the top performance rating in the Olympiad went to Georgian Ketevan Arakhamia, whose spectacular score of 12-0 exceeded Judit Polgar’s 10-2—not a bad result for anyone, but with Judit’s astronomical FIDE rating of 2555 her fans expected even more.

After the Novi Sad Olympiad, the three girls never again played together as a team. Judit, in fact, never played in another women’s tournament. The paths of sisters Sofia, Susan, a

nd Judit were about to diverge, both geographically and professionally.

Her sisters overshadowed middle child Sofia, sandwiched between pioneer Susan and prodigy Judit. She became less focused on chess and more interested in exploring life outside of chess. Although Sofia generally had the lowest rating in the family, she had no shortage of talent. An old trainer wrote, “I believe Sofia had a comparable talent [to Judit] and with some luck in the mid-eighties she might have had a similarly astonishing career.”6 When she was fourteen years old, Sofia had the result of a lifetime in an open tournament in Rome. Out of the nine rounds, Sofia won eight games and drew the last. Five of her opponents were grandmasters, and seven had higher ratings than Sofia, whose rating was 2295 at the time. This was one of the best performances of all time, enough not only for her to win the tournament ahead of top grandmasters, but strong enough to earn her the first of three norms required for the title of grandmaster. Her success caught the attention of the chess press—one headline screamed, “Super Sofia! Third Polgar sister lashes out in Rome.”

Over a decade later I asked Sofia about Rome. “It was a great performance on the heels of our victory of Thessaloniki, and my interest in chess was then at its peak,” Sofia recalled. “At the same time, my result in Rome was difficult to live up to, and it may have been too much, too soon.” Sofia’s triumph in Rome was to be her one and only great result. She never came closer to becoming a grandmaster. She grew out of her status as a child prodigy, and was uninterested in continuing her career by playing in women’s tournaments. Her level was not quite high enough to compete with the top male players.

Sofia met her future husband, Yona Kosashvili, a grandmaster and also a medical doctor, at a chess tournament. They married and moved to Tel Aviv, Israel. That Sofia, who was interested in so many things besides chess, married “someone involved with chess at all” was a surprise to older sister Susan. Living so far from both of her sisters and her beloved hometown was difficult for Sofia. “I miss Budapest, the architecture, and my own language. And most of all, I miss being together with my family.”

Sofia has never felt resentful or unhappy about her chess position in her family. Her other interests are important to her; she studies interior design and has a love for art and literature. Her favorites are Vincent Van Gogh and Czech writer Milan Kundera. “In other fields, just like in chess,” says Sofia, “women have not been allowed to rise to the top because of cultural constraints.” There is only one woman whom she truly admires: “I don’t really have any female role models besides Judit. When growing up, our parents taught us to believe in ourselves.” When I ask her if she is a feminist, she replies, “I am just an average woman of the twentieth-first century. I have my feminist ideas, but I also want to stay at home with my children as much as possible.”

The intensity and talent with which Judit approaches the game has made her unquestionably the greatest female chessplayer in history, so far ahead of any other woman in chess (her rating is between 150 and 200 points higher) that she has not even played one game against a woman in six years. “My attitude toward the game, especially in my youth,” Judit tells me, “could be called obsessive.” Her childhood was decorated with unprecedented achievements. In the same year that she scorched Thessaloniki, Judit became the youngest player of either gender to gain an international master norm. Also in 1988 Judit became the first girl to win a mixed world competition, the so-called Boys’ Under 12 Championship in Romania. And 1988 was only a typical year.

Judit Polgar, age 11, playing in the top section of the 1988 New York Open. (Photos by Gwen Feldman.)

As a preteen Judit began her quest for the highest title in chess, grandmaster. She was racing to break Fischer’s record in acquiring the grandmaster title at fifteen years and eight months. It seemed as if Judit was on track. A twelve-year-old Judit scored her first GM norm at the start of 1989, in Amsterdam, Holland, causing a sensation in the chess-crazed nation: “Polgaritis conquers Holland,” wrote Hans Kottman, a reporter for New In Chess, going on to describe Judit’s conduct at the board: “She smilingly rattled off deeply calculated variations, leaving her male opponents quite embarrassed with the situation.” Almost two years later, after many near misses, Judit scored her second norm in a round-robin tournament in Vienna. Judit had only one major tournament in which to score her last norm and break Bobby’s record: the 1991 Hungarian championship.

Both Judit and Susan played in the nine-round all-play-all national competition. Judit began the event with three draws: the first against her sister Susan—who performed well in the event, placing third—and the second and third against two veteran grandmasters of Hungarian chess—Portisch and Adorjan. Portisch’s irritating remark that “a woman world champion would be against nature”7 may have provided the additional and necessary motivation for Judit. Portisch realized that he was old-fashioned, pointing out that people once thought that no man would ever walk on the moon. However, a female chess champion, he said, would be an even less-likely circumstance.

In the second half of the tournament, Judit was unstoppable. At her level, having the first move was an enormous advantage, and in rounds four and six, she used the white pieces to devastating effect. Her opponents helped her by choosing very tactical opening variations, turning the games into the mad melees in which Judit was brilliant. By the last round, Judit had five points out of eight and was in a fantastic position.

A draw would clinch her the grandmaster title, but a win would earn her the title of Hungarian Champion. Would Judit play a quiet line in order to secure the draw or would she go for the tournament victory as well? She played the most uncompromising line imaginable. Navigating through the thicket of variations, Judit emerged from the scramble into a winning endgame. Her opponent, International Master Tibor

Tolnai, was twice her age. He resigned on move forty-eight: Bobby Fischer’s record was shattered. Judit became the first woman to win a national championship, and only the fourth women to gain the GM title.

Judit’s list of accomplishments started to read like a laundry list, as British master and chess journalist Cathy Forbes points out: “Reports of the Polgar sisters’ successes, at first astonishing, began in time to sound like a litany—repetitive and predictable….the repetitive refrain, symbolized by stark numeric scores, was only success.”8

After gaining the grandmaster title, Judit improved even more and advanced into the elite group of players rated over 2600. This score of players, the roster of which changes from year to year, now always includes Judit. For her, chess is a lucrative profession in which she battles the top men in the world in well-sponsored round-robin tournaments and rapid events in glamorous locations such as Aruba, Monte Carlo, and Buenos Aires. Judit is always in demand—she is the only woman in the world able to hold her own against the world elite. Judit’s presence ensures peak media interest, and her single-appearance fee is about $10,000.

Judit’s first success in a high-profile “super” tournament was in Madrid in 1994. She placed first in a strong field that included Latvian Alexei Shirov and Russians Evgeny Bareev and Sergei Tiviakov, all world-class players. New In Chess described her victims as “lamentable figures reminiscent of the gloomiest Goya pictures,” to which Judit added, “I am now eighteen and they behave as though they lost to a little girl.”9

Judit continues to try for more tournament victories. When I congratulated her on all her recent successes, she, like a true champion, reacted with customary dissatisfaction: “True, my rating has gone up, but it’s been ages since I won a tournament!”

Judit is notoriously reluctant to agree to interviews, so I was pleased that she had time to meet me for a one-hour interview. I took a cab to the greenest and most posh neighborhood in Budapest and walked up two flights to Judit’s immaculately decorated apartment, which she shares with her tall, dark, and handsome veterinarian husband, Dr. Gusztav Font. She met her husband when she took her dog to his office; he recognized her and asked her out for a g

ame of tennis. Among the decorations in Judit’s apartment are a fine collection of chess sets and a tiger-skin rug. I inquired about her veterinarian husband’s feelings about the rug, and Judit replied with a laugh, saying, “Oh, this is not his work. Don’t worry.” The two got married in Budapest in August 2000. Since then Judit has achieved some of her career milestones, beating Kasparov and breaking the 2700 rating for the first time. Judit, at the start of 2004, was ranked eighth in the world—a new height for her.

Judit credits her recent achievements to her happy marriage. “My husband supports me and works part-time so that he can travel with me to tournaments. You can even see that my playing style has changed. My life is more stable, and my play is more solid. Before I would sacrifice and lose a point, where now I would relax and make a draw.” Judit, especially in her youth, has been famous for her ruthless, verging on the reckless, attacks. But for her to compete with the world elite, it is necessary that she have a more universal style. “When I was younger, people would say my style was too aggressive, and I just didn’t understand what they were talking about!” That her victory over Kasparov was an endgame, where technique takes precedence over attack, is symbolic of her more balanced style.

Of the three sisters, Judit is the one who responds most negatively when I ask if she’s a feminist. “I’m not a feminist!” However, she has her own definition of the word: “In America I hear stories about women getting angry at men for holding the door for them or buying them dinner. I think women have the same mental capabilities as men, but I still like it when a man treats a woman as a man should treat a woman.”

Chess Bitch: Women in the Ultimate Intellectual Sport

Chess Bitch: Women in the Ultimate Intellectual Sport