- Home

- Jennifer Shahade

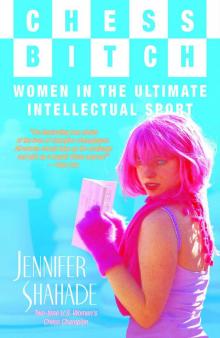

Chess Bitch: Women in the Ultimate Intellectual Sport Page 15

Chess Bitch: Women in the Ultimate Intellectual Sport Read online

Page 15

Xue Zhao. (Photo by Jennifer Shahade.)

In The Chinese School of Chess, Liu Wenzhe, however, argues that the Chinese do have a different style of play from Westerners. Liu Wenzhe explains that the Chinese tend to have a shallow knowledge of the opening, making up for this with a deep understanding of the middlegame and relentless fighting spirit. He points out that many of the Chinese players who were recruited by the government to learn to play international chess were brought up playing Chinese chess, xianqi and so there are some remnants of that game in their play. In Western chess, players often set up pawn structures early in the game. Pawn structures are locked formations, which rarely unravel, since pawns cannot move backwards nor capture forwards. In such closed positions, pieces are hemmed in by pawns, limiting tactical contact between the pieces and favoring long-term strategic ideas. Although the pawn is the weakest piece, they often determine the pace and nature of the game, causing Philidor, the great French player from the nineteenth century, to declare, “Pawns are the soul of chess.” In Chinese chess, on the other hand, pawn structures are less stable, resulting in more open positions, which require constant tactical vigilance. Wenzhe thinks that, as a result, Chinese players tend to be very comfortable in open games.

The Chinese women I asked were less sure that Chinese women play differently from other women. Xu Yuanyuan, a twenty-one-year-old woman grandmaster, said, “It’s all the same game.” If the Chinese do play differently from Westerners, the differences are subtle, especially in the highest circles in contemporary chess, where finding the right move tends to override individual style. Zhao Xue, the star of Bled, claims to have no preference for a particular type of game: “I like an easy position.” Professional chessplayers worldwide access the same chess databases, computer programs, and expert annotations, furthering the standardization of chess expertise.

It is hard to understand why state support of women’s chess in China was able to create a team stronger than the state-supported women’s team in the Soviet Union. The difference in ratings between the top male and female Chinese players is small compared to the differences between the Soviet men and women. The top four Chinese women at the time of writing are rated 2550, 2540, 2500, and 2500. The top male Chinese players have ratings that are on the average 100 points higher. In addition, the male players are about five years older. As the female players continue to improve, they could narrow the margin, or one day equal or even surpass the strength of the men. In Soviet teams, there is and always has been a much greater differential.

In the eighties and nineties, beginning with Xie Jun, Chinese chess trainers began to successfully train the women to play at the grandmaster level. Liu Wenzhe, the head coach of the women’s team since 1986, knew he had to replace the former leading players of China in favor of very young players who could be trained intensively from scratch. Raw talent was not that important, as he writes: “Systematically training players is more important than selecting them.” His program focused on middlegame study and careful scrutiny of a player’s own games. He criticizes programs that emphasize games of world champions above all: “It is a fallacy reflecting the obsession with celebrities.” By the twenty-first century, Liu Wenzhe was confident that he had achieved his goal, declaring: “The battle between the Russian and Chinese schools in the field of women’s chess ended in a Chinese victory.”

Almira Skripchenko offered her opinion as to why the Chinese women are stronger than the Soviet women: “The Chinese team, supported by the Chinese government, has a goal to become the strongest women’s team in the world. They will do what they need to do to reach this goal, just like the Soviets did what they needed to do to reach the pinnacle of women’s chess.” In order to win Olympiads, the Chinese had to have a team of girls strong enough to compete against the Polgars and the Georgian champions. The bar was raised, and the Chinese women climbed over it.

The success of so many Georgian women initially planted the idea that women could be great chessplayers if they had role models and training. The Polgars proved that it is possible for women to play at the highest level of chess, even though critics called them “exceptions to the rule.” The Chinese, in addition to the Polgars, are adding weight to the idea that women, in general, have equal chess potential to that of men.

The success of the Chinese women suggests that female chessplayers do not have different cognitive abilities from men, but rather that they are lacking a thorough and equally intense training program.

In explaining the development of a great player, one has to confront the controversy over just how important genius is. Overestimating the importance of genius understates the role of training and motivation. If genius were all-important, then the lack of opportunities for women in chess would hardly be relevant. After all, isn’t genius likely to override all circumstances?

8

Juno and Genius

When [a woman] thinks of a beautiful move, she is liable to think also about how beautiful she looks in making it.

— Leonore Gallet, prodigy musician and amateur chessplayer1

We invented genius so not to die of equality.

— French feminist writer Julia Kristeva

At the age of seventeen I believed that men and women had equal intellectual potential. However, when discussions about gender differences arose, I lacked the experience and theory to back up my ideas. I recall how frustrating it felt trying to hold my own in arguments like the one I had with a twenty-one-year-old grandmaster at the 1998 U.S. Open in Hawaii. He’d just lost his penultimate game to Judit Polgar, who was twenty-two at the time, utimately giving her first place in the tournament, which made her the first woman to win the title. Analyzing after the game, Judit joked around and tossed her hair while she zipped through one variation after another. The young grandmaster could barely keep up with her. Later he told me, “I lost because she is very well-trained,” adding bitterly, “she is no genius. Name for me one female genius; I can name hundreds of male geniuses.” I was pressed for the right words as he continued to goad me: “If women are as smart as men, why aren’t there any great female chessplayers?” I tried as best as I could to rebuff his claims, but failed. Four years later, after reading art critic and feminist Linda Nochlin’s essay “Why Are There No Great Women Artists?” in an art history class at college, I looked back on that argument and saw how I could have responded. Nochlin criticizes feminist thinkers who respond to the question of why there aren’t more female artists or geniuses by trying to name counter examples. She challenges the concept of genius that assumes “art is a free, autonomous activity of a super-endowed individual.” According to Nochlin, the greatness of artists develops when they are given proper training and financial and psychological backing.

The word genius derives from the Roman genius, a guardian spirit who watched over the birth of men and their works. The female counterpart, juno, who attended the women, would have been the alternate choice for genius. Later genius came to signify a person born with extraordinary intellectual gifts. The word genius is applied to either gender, but men still far outnumber women. In Genius, a recent tome by conservative cultural critic Harold Bloom, only thirteen women are included among the one hundred literary geniuses whose lives are profiled.

In Why Men Rule: A Theory of Male Dominance (1993) scholar Steven Goldberg is overt in his attempt to demonstrate the intellectual superiority of men. Goldberg, also the author of The Inevitability of Patriarchy (1973), is a professor and the sociology department chairman at the City College, City University of New York. “I suppose that those who explain the greater incidence of male genius in environmental terms have never had the fortune to be exposed to a mind of genius for long,” he writes. “Anyone who has will know that it is inconceivable that genius could be held back by social factors.” Goldberg suggests that anyone who disagrees doesn’t know any real geniuses. Nochlin, on the other hand, disregards first-hand experience (such as conversing with brilliant people) as relevant evid

ence, explaining that genius may “appear to be innate to the unsophisticated observer.”

Goldberg goes on to assert that no woman could ever reach the level of a strong grandmaster, a prediction that would soon be shot down by Judit Polgar.

Goldberg compares intelligence to height:

“Only males possess the extraordinary aptitude for abstraction that is a necessary condition for genius in mathematics and related fields [chess], and the fact that far more males than females possess the high aptitude for abstraction that is a necessary condition for near-genius in those fields virtually precludes the possibility of female genius in those areas and guarantees a preponderance of males in the genius group and at the near-genius level. This is perfectly analogous to height, a quality whose etiology is overwhelmingly physiological—all people over eight feet tall, nearly all people over seven feet tall, and the vast majority of people over six feet tall are men.”

Goldberg’s “perfect” analogy is dubious at best. Height is measured by a standard scale. There can be no debate that a seven-foot man is seven feet tall. Intelligence and genius are far more difficult to measure, and the criteria for geniuses are a tricky mix of objective achievement as well as subjective values.

I think passion can be mistaken for talent, or even genius. When I was a young girl, I was convinced that I had little talent for the game, because my father and brother were both much better than me. I was paranoid that people wondered why my brother was already a master and I could barely break even in lower sections. There were many reasons for my lack of progress. My motivation was less intense since I was intimidated by the skills of my brother and my father. Besides, I wasn’t having fun playing chess. When I reached middle school, the few girls I had hung out with at tournaments, eating Doritos and watching cartoons, dropped out of the game. I still played in tournaments, but I was not enjoying them nor was I improving. I began to shift my energies into theater and writing, figuring I would be the non-games player in the family.

My parents supported this move and encouraged me to go to theater camps and bought me books on Shakespeare. So one summer, as Greg played his usual schedule of tournaments, my mother drove me to upstate New York for a one-month intensive theater program. I didn’t like most of the classes, which were based on improvisational games that I disliked because they demanded that I be clever on cue. Despite being pricey and studded with the children of celebrities, the camp was overcrowded and I had trouble making friends. I felt left out of the clique of four girls with whom I shared a room. They talked about boys and shaved their legs sitting on the carpet. During my unhappy downtime at drama camp, I often lay on my stuffed mattress, obsessively writing lists of words in my journal—not difficult or provocative words, just adjective, verbs, prepositions, and nouns. It was as if I were suddenly overwhelmed by the vastness of language and wanted to encapsulate a chunk of it in a yellow spiral-bound notebook. My obsessive streak would soon find another outlet, in the study of chess openings. One evening my roommates confronted me for not including words such as love or kindness in any of the lists. Only a few hours later did it sink in that they had no business attacking me for not including certain words—I should have been angry at them for going through my stuff. But I avoided their eyes and shrugged, waiting for them to find something better to do. Perhaps if theater camp had been the creative and social experience I expected, I never would have gone back to the chess world, which I did soon after returning from camp.

My father wasn’t too much help at first. He thought the pressure of living up to Greg’s chess results would be too much for me. In one ugly incident when we were analyzing chess positions, he told me that I was improving quite slowly. I got so angry that I cursed at him and fled. At the door, I was still clutching Your Move, filled with the chess problems we were looking at. With hatred welling up for that book I tore its cover off. It felt so great that I continued, ripping out page after page, leaving a black and white mess of chess diagrams and variations on the gray carpet by the doorway. Recalling that incident years later, my dad laughed and said, “After that afternoon, she got good really fast.”

In the summer of 1994, a year after the theater camp, I went with my brother and father to Chicago to play in a two-week chess tournament. I was now thirteen, and hanging out with boys had become more fun for me. For the first time, I played blitz all night long and threw myself into my daily matches. My results and play improved immediately. Variations began to click and pieces danced into place. Sacrifices revealed themselves to me. Suddenly chess coaches and peers began to notice my talent. My dad also was stunned and impressed, taking me to tournaments, and arranging lessons for me. Obviously, I still had the same brain and the same neurons, but now I was motivated.

After Chicago I began to study the game seriously, on my own as well as with my schoolmates and my family. I would scrutinize my past games, looking for places that I played badly and searching for the reasons why I faltered. In this form, chess could measure my mind, which would sometimes expand to a size I wouldn’t have imagined possible, but at other times would contract, resulting in lazy play.

Post-game analysis has a rich tradition in the chess culture, and most tournaments have skittles rooms where players discuss their games freely. Moves that were discarded during the game for being too risky or just wrong are tried out in analysis, where pieces can be sacrificed at whim. If the combination doesn’t work out, the pieces are reset again, and another sacrifice is tried. Jokes and animated input from kibitzers replace the strict silence and head-to-head format of a tournament game. In the best cases, such post-mortem sessions become more satisfying than the game being analyzed, much like a Sunday brunch, where yesterday’s party breaks down over Eggs Florentine.

In the room I had lived until college, I have copies of notes to my old games. “Not patient enough,” I scribbled about one rash move. “I need to be more comfortable in waiting for something to happen.” I was hard pressed to resolve one inexplicable blunder: “I threw myself right into the rocks.” I did give myself credit for nice wins, though. In the notes to one win I wrote, “I was able to find the hammer blow right away.” This rigorous introspection has carried over into my life outside of chess, where I often dissect my own behavior in conversations and encounters.

I often wonder how different my life would be without chess. Many of the other selves I could have been might have been happier, less alienated, more politically active, and more likely to land in stable relationships and jobs. But without chess, I would be less confident and cosmopolitan, with fewer varied experiences and international friendships.

In China, a great chess tradition for women is greatly assisted by the government, which sponsors training and provides salaries for top players. The Georgian women of the former Soviet Union were offered similar resources. This type of support, both financial and psychological, is not common in the United States or Western Europe, where chess tends to be seen as an eccentric hobby, not a serious intellectual pursuit. Unless parents can pay for training or a child goes to a school with a chess program, American chessplayers (both males and females) are left to fend for themselves. Some nations offer stipends to talented players, but never in Europe or the Americas have the entire chess resources of a country been so concentrated as they were for Xie Jun’s monumental 1991 match against Chiburdanidze.

A player has to be very motivated to pursue chess in the United States or Western Europe. There are so many career options for an intelligent person to pursue that to play chess seriously requires a very passionate attraction—an attraction that could be called obsession.

Jennifer Shahade, 2000 U.S. Championship. (Photo by Val Zemitis.)

While it is viewed as normal for girls to obsess over clothes, weight, or men, it is not perceived as normal for them to obsess over chess.

As American Grandmaster William Lombardy pointed out, “Women are not as good at chess as men because they are more interested in men than chess.” A woman who

does spend all her time on chess is often seen as bizarre, particularly in places where a woman is expected to marry at a young age. Linda Nangwale from Zambia told me that women in her country are expected to be married by their early twenties. She wonders, “What kind of man is going to understand that I’d rather play blitz all night or study the Sicilian than hang out with him?”

The two greatest American players have reinforced or, to a certain extent, created, the image of a chessplayer as an obsessive genius. The first American chess legend, Paul Morphy, traveled to Europe in 1858, where he stomped on his opponents in brilliant style. He quit chess soon after returning to his hometown, New Orleans, where his madness bloomed. Wandering around the French quarter, talking to imaginary people, Morphy had already gone mad when he was found drowned in his bathtub in 1884. He was forty-seven years old.

Bobby Fischer, the ultimate symbol of individualism in chess, spent even more time on chess than a Chinese woman does, but he did it alone in his room in Brooklyn or in the hotels at tournament sites, surrounded by his stacks of chess books. Now Fischer, exiled from America for tax evasion, and has become a raving anti-Semite. Unlike the more glamorous, free-spirited eccentricity of a musician or an artist, the image of chessplayers like Morphy and Fischer is more often one of narrow, introverted weirdness.

Chess Bitch: Women in the Ultimate Intellectual Sport

Chess Bitch: Women in the Ultimate Intellectual Sport