- Home

- Jennifer Shahade

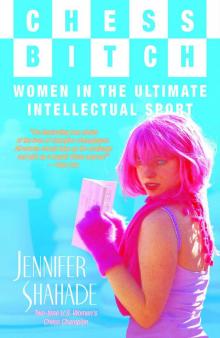

Chess Bitch: Women in the Ultimate Intellectual Sport Page 16

Chess Bitch: Women in the Ultimate Intellectual Sport Read online

Page 16

Fiction reinforces the stereotypes. Chess fanatic Vladimir Luzhin in Nabakov’s novel The Defense was unable to disentangle the events of the real world from the events on the chessboard. He became a great player, but his life ended in disaster when he threw himself out of a window.

Obsession may not be required for phenomenal success in chess, but it certainly helps. As a result, chess fever is romanticized, and some young players yearn to be more obsessed than they actually are. Harriet Hunt of Britain compared herself unfavorably to an ex-boyfriend, a grandmaster who was far more focused on chess than she was. “He would spend hours studying esoteric pawn endgames, and this really made me feel inferior and jealous that I was not as obsessed as he was. Women have this problem in chess, that we are not as obsessive as men.”

At tournaments, women may find it more difficult than men to completely lose themselves in the game and reach a zen-like state of total focus. That women are trained from a very early age to be constantly aware of how they appear may explain this.

John Berger, author of Ways of Seeing (1972), developed the idea of the “male gaze,” the feeling that many women have that they are being watched, even when alone. He writes, “A woman is almost continually accompanied by her own image of herself. Whilst she is walking across a room or whilst she is weeping at the death of her father, she can scarcely avoid envisaging herself walking or weeping. From earliest childhood she has been taught and persuaded to survey herself continually.”2 Such an extra layer of self-consciousness makes it hard to experience life directly or to feel pure freedom.

The male gaze is a psychological concept, a generalization that posits invisible differences in the way women and men think and feel. In chess, expert player Elizabeth Vicary thinks that women are also often watched in a very literal sense. As one of the few women in American open tournaments, Elizabeth and her games often attract a lot of attention. Although this can be embarrassing and annoying, it can also have positive side effects, according to Elizabeth. She feels that being mindful of their audiences makes women play more exciting chess.

Olympic women’s team coach, Grandmaster Ilya Gurevich, also believes that women are particularly conscious about what other people think about their games. “Women players are mostly worried about what their coaches will say after the game—usually men are just upset to lose.”

In the view of my coach, Victor Frias, putting in fewer hours is the main reason the best female players are not at the level of the best males. He praised Judit Polgar as the first woman to break into the world’s top-ten list, because she was “the only woman in chess who eats, sleeps, and breathes chess, just like her male counterparts.” Some feminists and writers agree that women do spend less time on chess, but think that the problem is not with women, but with the hyper-competitive structure of the chess culture. Alexander Cochburn wrote in Idle Passion, “It can be taken as a creditable sign that women have largely not become involved in chess or as expert as men in its execution, because they are happily without the psychological formations or drives that promote an expertise in the game in the first place.”

Anti-chess feminism, a way of thinking that I encountered time after time in my interviews and research, accepts Victor’s premise that women spend less time on chess, but don’t think this is a bad thing. As Margaret Mead said, “Women could be just as good at chess, but why would they want to be?” Nine-time American women’s champion Gisela Gresser considered men obsessed with chess bizzare. She said, “You know women are too reasonable to spend all their time on chess.”

Such rhetoric is not limited to the chess world. In the October 26, 2003, edition of The New York Times Magazine, the cover featured a woman sitting with her baby next to a ladder. The article by Lisa Belkin was titled “The Opt-Out Revolution.” The so-called revolution was about women leaving the work force to pursue more old-fashioned feminine roles. Sally Sears, a lawyer-turned-homemaker, said that women were leaving “the rat race” because “we’re smarter.”

That women might be too intelligent to waste their time on chess or work strikes me as a superficial idea. We reward excellence in most areas with money and respect, so to inquire casually if women are too smart to be obsessive requires a harsh assessment of our cultural values.

Surprisingly, some radical feminists would agree with conservatives that women and chess don’t mix well. Sexists might say that women aren’t playing chess because women are stupid, while “anti-chess feminists” might say that women aren’t playing chess because chess is stupid. Le Tigre, a radically feminist pop-rock band, wrote a song called “Mediocrity Rules,” with a CD cover that reads: “Behind the hysteria of male expertise lies the magic of our unmade art.” In this view, the existence of superstar figures such as grandmasters or rock stars are based on a patriarchal pyramid structure of power. The accomplishments and ideas of a few are celebrated, while the majority is overlooked. To replace “the hysteria of male expertise” it would not be sufficient to simply add a few women to the top of the pyramid, but to tear down the whole structure in favor of something more egalitarian and inclusive.

Chessplayers are definitely categorized with a pyramid structure, determined by their chess ratings. But this is not only a function of chess, but also the way the chess culture is setup, which could change in a way that valued participation and enjoyment in the game along with masterful play. In my career, I support ideas and organizations that broaden the appeal of chess, like coaching for Chess-in-the-Schools, which emphasizes participation over mastery, and in creating liaisons between artistic and chess worlds. Much more could be done. For instance, there could be tournaments in a larger variety of locations, and players could be invited based on factors other than rating, such as personality and chess style. There could be more prizes for beautiful moves rather than the current situation where—with the rare exception of brilliancy prizes (in which a panel of masters determine the most artistic games of the tournament)—all awards go to the winners. There could be more experimental matches in which the performative aspects of the game are highlighted, such as Marcel Duchamp’s match against musician John Cage, held in 1968 in Toronto. The two avant-garde artists designed and then played on a board on which each square was wired to respond to a move on it with a different eruption of sounds and images. Such measures could weaken the pyramid structure, and encourage less competitive types (both male and female) to try chess.

On the other hand, I profile the accomplishments of champions like Judit, Chen, and Nona because I believe that the focus and passion required to excel at chess is a beautiful thing. As long as there are winners and losers in chess, more prizes and attention will go to winners. And I think that’s appropriate, because winners tend to work harder on the game, have a deeper love for and understanding of the game, and deserve a greater share of accolades. Some of my fondest memories are of those periods when I was most engrossed in chess. Hours would go without my being aware of their passing as I played or studied intricacies. Losing track of time while immersed in chess fills me with a satisfaction so profound—for me the way being alive is supposed to feel.

9

European Divas

Sexy, self-confident, sociable…can we be talking about a professional chessplayer?

— Journalist Sarah Hurst on Grandmaster Stefanova

Nineteen-year-old Antoaneta was wearing a black wool jacket over her waifish frame on our way to a nightclub in a cab. The next day, Christmas 1998, was an off day from the tournament in Groningen, a Dutch college town. I was seventeen at the time and intimidated by Antoaneta, but after a couple of drinks I was loosening up and we began to talk. With her enchanting Bulgarian accent, dimpled smile, and quick wit, Antoaneta Stefanova has such charm that it is hard to meet her without wondering, How cool can you get? Already among the top ten women players in the world, Antoaneta—before hitting the dance floor—told me, “I prefer to beat men.”

Antoaneta (pronounced Antwaneta, and shortened by friends to“

Ety”) was born in 1979 in Sofia, the capital of Bulgaria, where, at the age of four, she learned to play chess from her father. Her remarkable talent for the game was clearly demonstrated when she swept the 1989 World Girls’ Under 12 Championship in Puerto Rico with a perfect score of 11-0. “I was winning all my games and very happy!”

Antoaneta extracts pure pleasure from winning, which I observed after playing her in a tournament in Spain a few years ago. Though an underdog, I was holding on to my position until she took a risk in mutual time pressure, sacrificing a pawn to gain control of the dark squares surrounding my King. This threw the game into a mad scramble. Under tremendous pressure, I eventually blundered. After the game, Antoaneta and I went to a restaurant with some Israeli friends. Glowing with the pleasure of victory, Antoaneta lingered over her tiramisu, luxuriating in what she calls “my fifteen minutes of feeling good about myself.”

Later in that tournament, I was introduced to Antoaneta’s sharp sense of humor. Waiting for a taxi outside a disco at around 5:00 a.m., Antoaneta impatiently complained: “When will this stupid fricking taxi get here?” causing one friend to tease her. “Ety—you’re so negative…” “Oh, sorry,” she quipped, “where is the very nice and highly intelligent taxi?”

Now in her twenties, Antoaneta Stefanova is one of the most active professional female chessplayers in the world. A typical yearly travel schedule (2002-2003) for Ety included trips to Argentina, Turkey, Russia, India, Israel, Indonesia, Curaçao, and nearly every country in Western Europe. Although Antoaneta usually prefers hot climates, she has recently added Iceland to her list of favorite countries. In the spring of 2002 Antoaneta and I were both there for the biennial Reykjavik Open, a strong international tournament. The Icelandic Chess Federation went to great lengths to support women players, inviting women from around the world and paying all expenses.

This was not my first trip to Iceland. In 1995, I played in a friendly chess match between American and Icelandic high-schoolers. I turned fifteen in the midst of the spectacular Icelandic celebration of New Year’s Eve. I was hanging out with teenaged Icelandic chessplayers, who were drinking beer while I sipped Coca-Cola. All over the country, families and friends gathered early in the evening to light roaring bonfires. By midnight the skies were lit up with fireworks. Iceland, a depressing place in the winter when days can remain black for as long as twenty-four hours, has one of the highest alcoholism and suicide rates in the world. One Icelandic master explained darkly, “In Icelandic winters, we don’t drink to have fun.”

Antoaneta Stefanova. (Photo by Victoria Johannson.)

This time, it’s March, and Iceland was on the cusp of spring. The event was held at the city hall in the center of Reykjavik. An hour early for my first game, I ordered an expresso in the café adjacent to the playing hall, where wide windows looked out on the icy landscape, and I could see school children skating on a pond. By the time of my last game the ice had melted.

Antoaneta had a below-par result in Reykjavik, but still managed to enjoy the virtues and vices of Iceland. The healthy lifestyle of fresh food included the finest salmon in the world. Clean, crisp Arctic air contrasted with the vibrant nightlife of smoky discotheques. We stayed at a mega disco till early in the morning, relieving the stress of six days of chess. Just before departing from Iceland, Antoaneta and I visited the famous Blue Lagoon Geothermal Pools, where tourists and locals bathed in the open air in all seasons. As the end of her stay in Iceland drew near, Antoaneta wasn’t sure she was ready to leave: “Iceland is one of the most interesting places I’ve been in a while and I would like to see more of it. But,” she added, “when I am in the same country for more than a week and a half, it feels strange, like it’s time to go.” At tournament’s end, she was off.

Antoaneta is unusual in the highest echelons of women’s chess in that she generally travels alone. I asked her why she rarely brings a coach, and she says that it is often prohibitively expensive. She also feels freer when traveling alone, explaining, “When I bring a coach I often feel more responsible for my results. I can easily become nervous and play badly.” Many coaches would also have problems with her free-spirited behavior. “I travel to chess tournaments ten months out of the year,” Antoaneta told me. “Wouldn’t it be a shame if I didn’t enjoy myself?”

If there is a discotheque near the tournament site, Ety is likely to be there, dancing to the pounding music and flashing lights. She smokes Cartiers and drinks Bacardis. Time permitting between moves, Antoaneta heads for the hallway, where she can puff on a cigarette while contemplating her position. When she was a teenager, Johnnie Walker sponsored her tournament expenses. Antoaneta has recently toned down a little. “When I was younger I used to be able to go out every night and still play well, but now if I go out more than two nights in a row it will show in my results.”

A major milestone for Antoaneta was to achieve the grandmaster title. She made her first norm during a trip to the United States by tying for second at the 1997 Hawaii International. The U.S. chess circuit was impressed by the young Bulgarian, who celebrated her eighteenth birthday during that tournament. In the weeks before Hawaii, Antoaneta had played in open tournaments in New York and Las Vegas on her first and only trip to mainland America, where she did not enjoy herself at all. She did not plan to return until she turned twenty-one, when she could legally enter bars and clubs.

Antoaneta struggled for a few years before earning her second norm in a round-robin tournament held in Salou, Spain. Her third norm came soon after in the 2001 Andorra Open, where she tied for first. She was awarded the title in 2002. At twenty-three, Antoaneta Stefanova became the eighth woman to gain the grandmaster title.

The twenty-first century found Antoaneta Stefanova among the highest ranked Bulgarian players, male or female. For the 2000 Olympiad in Istanbul, rather than agree to play first board on the three-board women’s team, Antoaneta accepted an invitation as a reserve on the mixed team. In Bulgaria, where the popularity of chess is similar to that of Olympic figure skating in the United States, an angry press attacked her decision. She could not think straight in Istanbul, Ety tells me, because of critics who wanted her to play on the women’s squad, where they thought she would contribute more points. Despite winning only three out of seven points in Istanbul, Antoaneta was able to play against tougher competition and was convinced she had made the right decision. “If I had to do it over again, I would do the same thing.”

As of June 2002, in spite of Antoaneta’s high ranking, she had never won a major women’s tournament. That year the European women’s championship was to be held in Varna, Bulgaria, a seaside resort lying on the shore of Varna Bay on the Black Sea, once a favorite spot of Bobby Fischer. The first prize of $12,000 attracted most of the top women players in Europe. Onlookers were rooting for Antoaneta, the hometown favorite. She would not disappoint. Antoaneta was in fine form, scoring 6.5 points from the first seven games. She eased into first place with draws in the last three rounds. The championship was the jewel in a crown of excellent results throughout 2002 and 2003. Her FIDE rating peaked at 2560, and when the April 2003 rating list was published, Antoaneta Stefanova had become the second-ranked woman in the world.

In the summer of 2003 Antoaneta discussed her recent successes with me, speaking with characteristic candor: “I made some good decisions in my life, for instance, moving my home base back to Sofia, where my friends and family are instead of living in some stupid place in Spain.” That place was Salou, a resort town near Barcelona. Salou’s spectacular beaches and discos provided good times as well as convenient access to strong European tournaments. But Antoaneta missed too many elements of her own culture and decided that she had to go back to her roots.

The adventurous spirit that sparks Antoaneta’s behavior also appears in her style over the chessboard, especially in her early years, when she liked to play offbeat openings. The lines were not theoretically challenging, but were likely to catch unprepared opponents off-guard and leave

them frustrated. “How could you live with yourself playing chess like this?” one opponent wondered out loud during a blitz game. Antoaneta was playing one of her favorite systems, the London, an extremely solid opening that is difficult for many players to fight against. “Oh believe me, I can live with myself,” she said and then proceeded to crush him. Antoaneta now plays more conventional lines, and writes off her earlier opening strategies to laziness. “At some point I just realized I didn’t have the discipline to study the main lines in depth,” she said. She believed her natural skill would give her an edge and that she would score more points with sidelines.

Antoaneta’s strength, both over the chessboard and in her personal life, has allowed her not only to survive in the male-dominated arena of European Open tournaments, but also to thrive there. She told me, “I’d rather do feminist things than talk about feminism.” Antoaneta is not afraid to confront tournament organizers and journalists, as I discovered when interviewing her. At the time, a question I’d used in other interviews seemed entirely reasonable to me and so I asked her, “What is your favorite [chess] piece?” Even though Antoaneta and I have been friends since we met at a tournament in 1998 in Holland, she gave me a withering look as though I’d gone mad, then said, “I can’t believe that you—as a chessplayer—asked me that.” She added, “When journalists in Bulgaria ask me questions like that, I tell them to learn something about chess and then come back for an interview.”

At least I didn’t make the mistake of trying to interview her too early in the day. Antoaneta, who usually prepares at night and sleeps until just before a game, was outraged when an organizer once tried to schedule an interview for her in the morning. “What—they want me to get no sleep and lose my game?” The interview was rescheduled.

Chess Bitch: Women in the Ultimate Intellectual Sport

Chess Bitch: Women in the Ultimate Intellectual Sport