- Home

- Jennifer Shahade

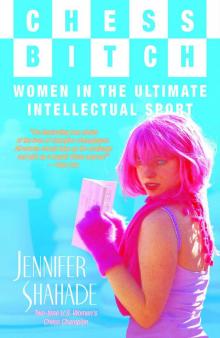

Chess Bitch: Women in the Ultimate Intellectual Sport Page 6

Chess Bitch: Women in the Ultimate Intellectual Sport Read online

Page 6

Maya Chiburdanidze (1982).

Maya is often called the first prodigy of women’s chess. Prodigies are common to chess, math, and music, all abstract endeavors in which competence does not require adult experience. In chess, the energy of youth often balances the wisdom of older players. The young are also more likely to have the time and inclination to spend countless hours studying and weeks competing in tournaments.

When Maya was ten, her family moved to Tbilisi, where Maya would be able to improve her skills and face better competition. She played incessantly. As an eleven-year-old, she competed in twelve different week-long events in one year. The intensive training and playing program was effective. At just fifteen, Maya won the USSR championship, ahead of two former world-champion candidates (Kushnir and Alexandria). The victory was not only a remarkable achievement in itself, but also gave Maya the opportunity to challenge Nona two years later.

The World Championship match was held in Pitsunda, Georgia, a resort town on the coast of the Black Sea. Despite Chiburdanidze’s obvious talent, the experienced, determined Nona was still the favorite. Three tense draws began the match. In the fourth round, Maya won in thirty-four moves with the black pieces, punishing Nona harshly for an ineffective opening strategy followed by very poor middlegame decisions. Nona was shell-shocked. An energized Maya won the next game as well. In the latter half of the match, Nona narrowed Maya’s lead by winning three games to Maya’s two. In the final game Maya had the white pieces and needed only a draw to dethrone Nona. The course of the last round game could not have been more dramatic. Maya, under tremendous pressure, played too passively and Nona won a pawn and simplified into an endgame. After a ninety-four-move struggle, Nona was forced to yield a draw to Maya’s determined defensive fortress, bringing to an end the reign of Nona, de facto Queen of Georgia.

By defeating Nona, Maya became, at the age of seventeen, the youngest world champion in history, too young to fully understand her victory. One observer remarked, “Maya was pure genius. She just loved the game, but had no idea of the historical import of what she had done. After she won the match, she went to her room to play with dolls.”

There is no prototype for the temperament of a champion. Maya and Nona are very different from each other. While Nona’s energy emanates outward, Maya’s is more introspective, giving her a meditative glow. She is deeply religious. Like many Georgian Orthodox Christians, she often wears a headscarf. Romanian IM Corina Peptan admires Maya’s modest demeanor: “She is not concerned with her image, and prefers to stay in the corner. She is a star in chess, but she does not need or want attention.”

Maya Chiburdanidze, Erevan Olympiad (1996).

The personalities of the two women carry over into their chess styles. Nona is aggressive, even ruthless, while the mysterious Maya is patient and strategically minded. “You could never predict Maya’s moves” said one contemporary, “Nona—you could be sure she would choose the most aggressive option.” Nona pushed too hard in the Pitsunda match, and it was her hasty, overwrought decisions that cost her points. Judging from the style of the games, a master would surely guess that Maya was the veteran and the impetuous, aggressive Nona the youngster.

Maya defended her title four times. In 1981 she played against Nana Alexandria, who’d previously lost in the battle of the Georgians, Nana versus Nona. This time Alexandria played very well and managed to tie the match. But the rules state that in the case of a tie, the champion retains her title. Maya’s next successful defense was against Irina Levitina from Russia, who now lives in the United States and is a professional bridge player. With two rounds to go the women were even, then Maya rallied and won both games. Her third and fourth world-championship victories—in 1986 against Siberian Elena Akmilovskaya and in 1988 versus compatriot Nona Ioseliani—went more smoothly. Elena (now Donaldson) has dismal memories of her games against Maya. “When I first played Maya, I was fourteen years old and she was just a chubby little girl of eleven years old who stared at the ceiling for most of the game. But staring at the ceiling, she began to make spectacular moves and it became clear to me immediately that she was a genius. I could never get over this young loss to her, and my lifetime record against her has been horrendous. The match was a catastrophe.”

Maya’s own reign finally ended in 1991, in a surprise upset at the hands of the Chinese player Xie Jun. According to Maya, losing her world title made her hungry to reclaim it. In the past decade, she has come close, but failed to regain her title in six attempts.

Nona Gaprindashvili and Maya Chiburdanidze were the only two Georgian women to achieve the ultimate women’s title of World Champion. Nona and Maya inspired many players, and the Georgian women’s chess culture grew. Nana Alexandria and Nana Ioseliani both lost world championship matches by narrow margins. Although they never enjoyed the fame or success that Maya and Nona did, they helped to establish the great tradition and international reputation of women’s chess in the tiny country of Georgia.

Every two years players and fans look forward to the most prestigious chess team event, the Olympiad. The first Olympiad was held in London in 1927, but fielded only male teams, while women played individually in the first ever Women’s World Championship. Starting from 1957, the Women’s World Championship was organized separately, and women’s teams entered the Olympiad. Each participating nation selects four players for its women’s Olympic team, three of whom play at any given time while the fourth sits out.4 The team result is derived from the individuals’ combined records. Georgian women were selected most often for the Soviet team, but there were talented contenders from other parts of the USSR, including Elena Akmilovskaya, who played for the 1986 world title, losing to Maya.

Elena Donaldson, 2004 U.S. Championship. (Photo by Quinn Hubbard.)

Elena was born in Leningrad, in 1957. Although chess was not popular in Siberia, Elena’s mother, Lidia, was a strong player and taught her eight-year-old daughter the rules. Elena says, “My mom was everything in my chess development. We played blitz every day and I got mad when I lost.” When she turned twelve, Elena had the opportunity to be introduced to the wider chess community. Twice a year, the most talented young players in the USSR met in Moscow to spend a week at a special training academy, run by World Champion Mikhail Botvinnik. Among the students of the school was a future champion, Garry Kasparov, who later wrote glowingly of his experiences there. Elena’s own experience was abruptly interrupted. At the age of sixteen, she was not invited back, because of her recent mediocre results.

Temporarily disenchanted with chess, Elena turned her attention to her university studies, which were biophysics and mathematics. She did continue to play, however, and to her surprise, had a breakthrough tournament in the 1975 Soviet Women’s Championship. Elena gave up biophysics and math and switched to law in order to devote more time to studying and playing chess. “Chess never came easily to me. I always had to train very hard for good results.”

Elena’s renewed confidence and personal motivation gave her the strength she needed to confront the Georgians. To them, Elena was something of an outsider, and was not readily welcomed into their circle. At the Candidates Tournament in 1978, held in Tbilisi, the Georgians went to extraordinary lengths to slow Elena’s progress. A Georgian man, “incredibly gorgeous” by all accounts, showed up at the tournament. The man, Vladimir Petukhov, showered Elena with flowers and presents. Elena suspected he was a plant to distract her from her games, so that the Georgian women would prevail. “It may have been a distraction,” noted an observer, “but they fell in love and got married, and Elena ended up playing Maya for the world championship anyway, so it must have been a positive distraction!” Vladmir lived in Tbilisi. Elena transferred to the university there and married him. She divorced him in 1986 after seven years of marriage and one child, Dana.

At the time, another romanance was burgeoning for Elena, with American John Donaldson, an intelligent and affable international master from Seattle. They met at a to

urnament in 1985 in Cuba, where Elena was playing and John was coaching. Their contact should have been limited because of the scrutiny of the Soviet authorities; however, “As luck would have it,” John recalled, “Soviet security was very lax.” The two spoke cautiously about uncontroversial topics such as opening variations. “We felt severely constrained in saying what we wanted to say,” John explained. “We didn’t want to attract a lot of attention.”5

Elena and John continued to see each other at tournaments around the world. At the 1986 Olympiad in Dubai, they met at a disco every night. Their behavior was noted by the Soviet authorities, one of whom gave Elena an official censure for associating with a Westerner. Elena was warned that if it happened again, she would be barred from playing outside the Soviet Union.

In the 1988 Thessaloniki Olympiad, Elena’s romantic and professional ambitions were destined to collide. The Soviet team had to contend with a formidable Hungarian team’s rising stars: Susan, Judit, and Sofia Polgar. Maya Chiburdanidze was first-board on the Soviet squad, the sole Georgian on the team—the first time in years that the Soviet team was not dominated by Georgian women. The contest between the Hungarian and Soviet teams was tight throughout the event. Judit Polgar and Elena Donaldson were the high-scoring stars of their respective teams. With three rounds to go, both women were playing at the grandmaster level with staggering performance ratings of more than 2600. On the day of the eleventh round, Elena failed to appear for her game. That morning she left her team to elope with John Donaldson, who was there as captain of the United States team. American players cheered on the couple, and it became the fairy-tale story of the tournament. The darker side is that Elena did desert her team, a move that would likely be harshly criticized if it were made by a man. She had performed brilliantly, earning 8.5 points from nine games. In the final three rounds, the now-weakened Soviet team lost to Hungary by just half a point.

This loss was symbolic of the end of Soviet domination of women’s chess. Elena’s abrupt departure foreshadowed a great migration of Soviet players to various corners of the world, especially that of Russian Jews to the United States and Israel. Fifteen year later, remarried to IM Georgi Orlov and still living in Seattle, Elena continues to regret her decision to leave in the middle of the tournament: “I cried when I read the news that the Polgars ended up winning the gold medals. Now, it is clear that with the disintegration of the Soviet Union soon after the Thessaloniki Olympiad, I could have left the country easily without abandoning my team. But at the time, there were still KGB spies traveling with us, and I had no idea whether I would get another chance to escape the country.”

Since the break-up of the Soviet Union in 1991, the economy in Georgia has suffered enormously as a result of corruption, damaged infrastructure, and an economy that relied heavily on imports from other Soviet republics. In 1994 the unemployment rate was estimated at 1.5 million, nearly half of the Georgian working-age population. As a result, one million Georgians, almost a fifth of the population, have emigrated. The situation for Georgian sportspeople, who were well supported under the Soviets, has also deteriorated, and among the one million émigrés are several prominent chessplayers. This exodus has naturally loosened Georgia’s stronghold in women’s chess. In the 1992, 1994, and 1996 Olympiads, the Polgar squad had dissolved, and Georgia won each Olympiad impressively—the same players who had dominated a decade earlier, including Maya and Nona, were still playing successfully. But countries such as China and Russia, with younger squads, were closing in on the Georgian dominance.

The economic problems in Georgia have resulted in the departure of some of the most talented young players—those who had fewer personal and professional roots in Georgia. Among those who emigrated are youth champions Tea Bosmoon-Lanchava and Rusudan Goletiani, who moved to Holland and the United States, respectively.

I have become friendly with Rusudan throughout our meetings as members of the U.S. Women’s Olympic Team. Rusudan calmly told me about her dramatic childhood. She grew up in Abkhazia, a region in northwest Georgia where civil war erupted in 1992. Tipped off by a KGB agent of the upcoming civil chaos, Rusa and her family fled the region for Tbilisi with only the clothes on their backs. “It was awful; the plane was crammed full of people and everyone was crying.” Rusudan was one of more than 200,000 ethnic Georgian refugees to flee from Abkhazia in the years 1992-1993. Rusa and her family slowly built up a life in Tbilisi, but making money in Georgia was difficult, and in 2000, Rusa jumped at a chance to move to the United States.

Rusudan Goletiani. (Photo by Jennifer Shahade.)

Friendly and magnetic, Rusudan had no problem fitting in New York, especially not in Brooklyn, where she first landed: “I was shocked to see how many Georgians are living in New York. When I first moved here to Brighton Beach, I would constantly hear people speaking Georgian.” Her heart is still in Georgia, but the economic situation keeps her in the United States. “Ever since the break-up of the Soviet Union, there has been no government support for chessplayers. So if you want any money to play in tournaments, you have to go to private sponsors and you have to self-promote, and this is not for me.” Rusudan sends a large part of her monthly take-home pay back to family and friends in Georgia: “I would rather that a friend has money for food than to have a new pair of jeans.”

Rusa began her life in the United States living in Coney Island and baby-sitting. When her English improved, she moved to Westchester, New York, where she now teaches chess. Goletiani makes in an hour what she could make in a month in Georgia by giving lessons in posh homes, but she does not feel that Americans respect chess. “In Georgia, if I was training for a tournament, the teacher would allow me to concentrate all my efforts on chess, but here in America nobody takes chess seriously. They see it just as a game, whereas for me it is like a small model of life—the middlegame in chess is like being middle-aged and you have to decide on the right plan.”

Tea Bosmoon-Lanchava is six years older than Rusa and shares Rusa’s ambivalence about leaving her beloved Georgia. Tea’s first years as a chessplayer were like those in a fairy tale. Her role model, Nona Gaprindashvili, discovered her at the age of nine when she was brought by her uncle to play against Nona in a simultaneous exhibition. Nona recognized Tea’s talent and instructed her parents that she should move to Tbilisi in order to train. Tea describes those days as the best of her life. “Nona and I would train for hours and she would tell me stories until I would look at the window and notice that it was getting dark. I would forget hunger, time, thirst.” Tea won two World Youth Championships for the Soviet Union. “I’m really nostalgic for the Soviet days. I was lucky to see the last days of how much support you could get as a Soviet sportsperson.” Now Tea lives in Holland with her husband and child; she still plays chess, insisting that she will never quit “because it is in my blood. Everyone is always asking me about how frequently I travel, when I have a husband and child. Sometimes I feel like telling them to shut up and allow me to live my life. I love chess and I can’t quit.”

Most of the older players have remained in Georgia, including Nona and Maya, who still enjoy celebrity status. Nona Gaprindashvili, now in her sixties, has lost a couple hundred rating points since her peak, but she keeps playing. She takes her games very seriously, and if she loses she still becomes visibly upset. At the 2003 European Women’s Championship in Istanbul, she would play Yahtzee for hours. I hung around the table watching her play for a while, hoping to ask her a few questions, but Nona was totally wrapped up in the dice.

In the 2002 Olympiad in Bled, Slovenia, the Georgian team was poised to recapture the gold medals, which had fallen into Chinese hands for the past four years. After ten rounds Georgia was ahead by three full points and, under normal conditions, would be able to glide gracefully into first place. But disaster struck. Ketevan Arakhamia had “never seen anything like it. It was as if nobody could win a single game.” The terrible performance of the Georgian women in the last few rounds left them off the podi

um, and allowed the Chinese to gain top honors for the third time in a row. Judging only by the Olympic team members, three of whom were over thirty-five, you’d think that Georgian women’s chess was a tradition of the past. In reality, Georgia is still producing many great talents, including the 2003 World Girls’ Champion, Nana Dzagnidze, along with Maia Lomineishvili and Ana Matnadze. These women, all in their teens and early twenties, often have to take backseats to the more experienced and higher-ranked Georgian women at the prestigious tournaments. But the energy of youth can trump higher ranking, especially at long and exhausting tournaments. Nino Gurieli, president of the Georgian Chess Federation and past member of winning Georgian women’s Olympic teams, is dedicated to promoting the younger generation: “The team that played in Bled was the Georgian women’s team of the twentieth century. From now on we need to support the team of the twentieth-first century.”

In the fall of 2003 I called Nana Alexandria, the former world championship candidate turned chess politician, who is fluent in English. She answered her phone in Georgia and, though courteous, was short with me. “Can’t talk now,” she said, “there is a revolution going on outside.”

Chess Bitch: Women in the Ultimate Intellectual Sport

Chess Bitch: Women in the Ultimate Intellectual Sport