- Home

- Jennifer Shahade

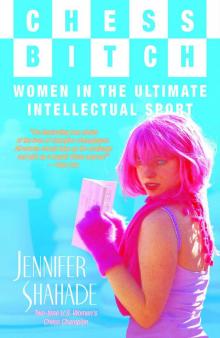

Chess Bitch: Women in the Ultimate Intellectual Sport Page 7

Chess Bitch: Women in the Ultimate Intellectual Sport Read online

Page 7

In November 2003 the bloodless Revolution of Roses ousted president Eduard Shevardnadze, who had led Georgia since the Soviet era. He was replaced by opposition leader Mikheil Saakahsvili, a thirty-nine-year-old progressive. The next time I saw Rusudan Goletiani in New York, she was beaming. “All my friends and family are thrilled,” she said. Rusudan is cautious about predicting how Saakahsvili’s election will affect her future, but she hopes for political reforms that will allow her to return one day to Georgia, where both her family and her husband’s remain.

4

Be Like Judit!

When I first found out that the J in J. Polgar stood for Judit, I was so excited. I didn’t even know she was a woman, just that she smashed her opponents like mashed potatoes. After that, I put her games up on my bedroom wall.

— Linda Nangwale from Zambia

Nona’s successes and character influenced the younger women of Georgia, many of whom cite her as a role model. “It all just kept rolling after Nona won the title. She was the first, and many followed,” says Rusudan Goletiani. Nona’s fame was unprecedented: girls took up chess instead of enrolling in ballet school; fans would wait to greet Nona at the airport; people would stop her on the street for her autograph; many even named their girl children after her. A statue of Nona was erected in her hometown, Zugdidi. On her sixtieth birthday, the Georgian government awarded her two cars.

Stretching the limits of what was possible for Georgian women, Nona’s influence extended outside chess. “Nona began an intellectual revolution.” said Rusudan “She turned everything upside down. She was always beating men. If women could be good at chess, they could be good at anything. Nowadays Georgian women are more involved in politics, science, and art. They do not like to sit at home anymore. It used to be more common for women in Georgia to get married as young as seventeen or eighteen, but now they are encouraged to become professionals before getting married and starting a family.”

Rusudan Goletiani’s father used to show her newspaper clippings about Nona, Nana, and Maya, which she would read hoping “that one day I would become a great player myself!”

The stars of women’s chess in Georgia were particularly powerful role models because they were both accessible and exceptional. Georgian girls could read about them in dailies, meet them at exhibitions, or go to tournaments to watch them play. At the same time Georgian women were international heroes, breaking records and winning championships. Tea Bosmoon-Lanchava laments that trying to develop women’s chess in Holland is not easy because the girls do not have such national role models to follow.

When Linda Gilbert, a doctor in psychology, surveyed American chessplayers, she found that the most influential role models were accessible figures such as coaches, teachers, and parents. According to her study, when fathers were highly educated, only the sons excelled in chess, but when the mothers were highly educated, both girls and boys excelled. Whether the mothers were chessplayers made no difference. Successful mothers seemed to transfer their professional ambition to their daughters.

My own experience meshes with Gilbert’s findings. My father taught me the basic moves and rules of the game at an early age, later advising me on the intricacies. My mother’s role in my development as a chessplayer, though less direct, was just as crucial. She was a professor of chemistry (Dr. Solomon), an avid games-player, a skilled writer, and a gourmet cook. My mom always seemed to be excelling at three or four things at once, all the while having a great time. My mother once claimed that her birth year—1940—made her the perfect age to enjoy the sixties to their fullest. Still, she was more serious than many of her peers—despite participating in the protests and the parties she wanted a stable career and financial independence.

She never put too much direct pressure on me, but I understood from an early age that to her, succeeding in male-dominated endeavors, being independent, and having the means to be generous were important values. Still, there were things I rejected. The main point of contention between us was my more-relaxed view toward money and a stable future. The tension settled suddenly as my fame in the chess world increased. I appeared on the cover of chess magazines and was profiled in Smithsonian magazine. My mother, as well as many friends of the family and relatives, suddenly stopped asking me when I was planning to apply to law school. This delighted me, though I sensed it was based on a misconception that media recognition was lucrative—as if magazine spreads could be endorsed and cashed.

Asking interview subjects about role models is complicated because the concept of a role model is both semantic and deeply personal. When questioned about role models, many of the women I interviewed seemed uncomfortable with the idea and declined to name any. Rebuffed again and again, I began to see that role models to them carried with it a negative connotation, equivalent to idol worship. If I wanted answers, I needed to find a different way to ask my question. Almira Skripchenko had already denied having a role model, but when I asked her which women she admired, she had no problem coming up with tennis player Steffi Graf, philosopher Ayn Rand, and Grandmaster Judit Polgar.

The women who were willing to name a role model gave a diversity of answers, often choosing someone they had never met. Some cited men, such as Anna Hahn, who chose a fellow Latvian player, World Champion Mikhail Tal. Zhu Chen told me her role model was Wu Zeitan, the Chinese empress from the sixteenth century. There was only one person, a chessplayer, who was named again and again.

Hungarian Judit Polgar, the best woman player by a wide margin, has had a global impact that extends to girls from five continents. Ecuadorian Evelyn Moncayo said, “I have admired Judit since I was nine years old and saw her beating up on all the boys in the World Youth Championships in Wisconsin.” Judit made her realize she could compete against boys.

Irina Krush, like Evelyn, began her chess career at the time that Judit Polgar was cementing her position as one of the world’s best players, female or male. I remember a twelve-year-old Irina telling me once, “What I would give to be Judit Polgar, for just a day.” Recalling this declaration, I was surprised when in response to my question about role models, Irina understated Judit’s influence on her: “I admire Judit Polgar, but not in a different way than Karpov.” Perhaps Irina had honestly forgotten how she had once felt about Judit Polgar. Irina may also have realized that having Judit as her role model would interfere with her own ambition. Irina, on her way to becoming a world-class player, must only want to be Irina. Alexandra Kosteniuk, the young Russian grandmaster, articulated it best: “I have no heroes in chess. Maybe that’s because I want to become a hero myself.”

Free-spirited Bulgarian Grandmaster Antoaneta Stefanova cites no role models, although she does describe having a youthful fascination with Bobby Fischer, as did fans all over the world, especially young men. Fischer’s victorious match with Spassky in 1972 caused an enormous increase in the popularity of chess in the United States as the general public—not just chessplayers—eagerly awaited the results of their every game. Fischer became a symbol for the superiority of individualistic American ingenuity over systematic Soviet training methods. Fischer’s skills as well as his good looks and quirkiness were admired, while his poor manners and bizarre demands were accepted as part of the package that made him great. Fischer’s awesome feats in chess made it too easy to underestimate his early signs of madness. His descent from American hero into a raving, uncouth anti-Semite was chronicled by journalist Rene Chun in “Bobby Fischer’s Pathetic Endgame,” published in 2002 in The Atlantic Monthly. The danger in equating achievements with character is exemplified by Bobby Fischer; his worshipers were forced to shed their admiration for the man himself.

For women it is often problematic to have male role models, since the desire to be like a great man can easily be confused with the desire to be with a great man. As a teenager and rising chessplayer, I remember trying to distinguish between the two. At the time I found strong chess players sexy, but wrote in a journal that more than having crushes o

n them, I wanted to crush them!

Such paradoxes seem to abound in the chess world. Indian-born American chessplayer and coach Shernaz Kennedy was inspired by Bobby at a young age. The first book she picked up was Fischer’s My 60 Memorable Games, and she was immediately intrigued by his clear-cut victories and lucid writing style. She began to carry a picture of Fischer in her wallet. (At the time of writing, coincidentally, there is a photograph of artist and master chessplayer Marcel Duchamp in my wallet.) Later Shernaz even became a close friend and confidante of Fischer’s. Shernaz played competitively for years, until settling into her current job as a high-end chess coach. I met Shernaz, her arms overflowing with shopping bags from ritzy boutiques, at a café on Park Avenue. As we chatted over iced cappuccinos, raven-haired Shernaz joked to me: “When I was young, I only wanted to date guys who looked like Fischer!”

Many women chessplayers find the prospect of dating a player weaker than they unpalatable. “I would just as soon date someone from outside the chess world than a weaker player than I,” said Anna Hahn, who likes “men who are good at what they do.” Young German star Elisabeth Paehtz also told me she is attracted to strong chessplayers, though she would be reluctant to date anyone too good. “A player over 2700 is likely to be crazy!” she jokes.

There is nothing unusual about wanting to be with a man who is good at what he does. Elizabeth Vicary, a chess expert and coach from Brooklyn, has always been attracted to strong chessplayers and is unapologetic about it. “There must be some reason to be initially attracted to someone, and I admire people who are good at what they do. Liking someone for their chess strength is not as superficial as liking them for their appearance or money.” Elizabeth says chessplayers are often “intelligent, imaginative, and hard-working,” and also less likely to be “entranced by fame and money.”

In chess, the Elo rating system clearly delineates worth. Top British woman player Harriet Hunt says that very early she realized that her chess rating was an important part of who she was. Until recently the international rating system has assigned ratings that ranged from 2200 to 2800. In 2000 the system was amended, and international ratings, as they do in the United States Federation, go as low as 100. Rating denotes value to such a large extent that one grandmaster compared losing ten rating points at the top level to losing ten liters of blood. A high chess rating is a status symbol. Many people refer to opponents not by their names but by their ratings: “I am playing a 2250, or I lost to some 1500,” since the number becomes a more crucial mark of identity than a name. At the highest levels, names are obviously used, and no chessplayer would say, “I am paired against some 2700.” After all, there are fewer than twenty players rated over 2700, and part of the deal in becoming that strong is that you do get your name enshrined.

That the chess rating system presents value in such a stark, numerical way leads to some difficult questions for women. Does the desire to be with a strong man conflict with the desire for a woman to be strong herself? Is sleeping with someone who is a great player a consolation for not being a great player oneself? Elizabeth Vicary thinks that her own motivation was squashed, partly because as an attractive woman, she was already a star in the chess world. “As a young female 1900 in the chess world, I got so much attention—which seemed like respect—from all the best players that my incentives to improve were less. If I were a guy, the only way I could have gotten such attention would be to study all the time.” Proximity to greatness becomes a substitute for greatness itself.

There are countless examples of chess relationships in which a male grandmaster is with a talented, but weaker, partner: beginning with U.S. Women’s Champion Mona Karff and International Master Dr. Edward Lasker up to and including today’s couplings between elite Grandmaster Alexei Shirov (27301) and Victoria Cmilyte (2450), or the now-broken marriages between Almira Skripchenko (2500) and Joel Lautier (2700) and Alisa Galliamova (2500) and Vassily Ivanchuk (2750). And these are only the high-profile examples, where the talent in the relationship is phenomenal and the female players are chess stars in their own right. The tendency for women to choose the top male players is partly because of the skewed female/male ratio at chess tournaments—so few women play chess that they usually have a choice between many suitors. “Why not pick the strongest?” asked American player Diana Lanni. This phenomenon also occurs in less male-dominated subcultures. My mother, Sally Solomon, pointed out that at bridge tournaments—where the male-female ratio is far more balanced—“whenever you see a weaker woman player with a top man player, everyone begins to whisper that they are sleeping together. And most of the time they are!”

Victoria Cmilyte’s marriage with Alexei Shirov is the strongest and tallest union in chess history (both are over six feet tall). The two met at the 2000 Istanbul Olympiad in which Shirov was immediately taken in by the smiling, radiant woman. In the tournament, she won game after game, earning a gold medal on board one. At the time, she was only eighteen years old, and had already won the mixed Lithuanian Championship. She was one of the best young players in the world of either gender, and naturally she had already studied the games of Shirov, one of the most thrilling figures in modern chess, a brilliant tactician and fighter. (His book of games is titled Fire on Board.)

Cmilyte said that her initial attraction to Shirov was largely based on his stature in the chess world. However, she insists that after a few weeks something more “substantial” such as love is needed to sustain a relationship. A few weeks after meeting in Istanbul, Cmilyte and Shirov both played in the 2000 World Championship in New Delhi, India. Cmilyte got knocked out first, but she stayed on to support Shirov, who proposed to her during this tournament. A few months later, Cmilyte and Shirov were married and they soon had two children, Dmitri (2002) and Alexander (2004). I caught up with the young mother recently, who told me that she does not study chess too often with her husband, but he does help her at tournaments with her opening preparations. Still, it is clear when talking with Victoria that the focus in the family is on Alexei’s chess career: “It’s very hard to maintain his level at the top of the chess world.”

Men are sometimes also attracted to powerful and intelligent women. In the chess world there are examples of couples in which the strength of the players is equal, as in the marriage between Mohamad Al-Modiahki and Zhu Chen, both of whom are rated about 2500. Or the young couple Irina Krush and Pascal Charbonneau. The generally amiable International Master Almira Skripchenko was clearly annoyed when I asked her whether women had less incentive to get strong for fear of intimidating men. Attractive, charming, and confident, Almira has always received attention, but she does not believe that her chess strength detracts from this. “Guys are impressed by chess skill; it’s ridiculous to think they’d be turned off by it.”

Other women players maintain that men are intimidated by smart women. Olga Alexandrova, a grandmaster from Russia, ranked as the thirtieth woman in the world, declared in an interview that the worst thing about being professional women players is that “men are afraid of us!” When she meets a man, she keeps her profession secret for as long as possible. She finds it unusual for a man “to appreciate intelligence. . . there is a common stereotype that if a woman plays chess she is either abstruse or crazy.”2 This reminds me of an episode of Sex in the City where the powerful law partner Miranda, beautiful but luckless in love, guesses that her power as a law partner is intimidating men. So she starts lying to guys, telling them that she is a flight attendant. Lo and behold, their interest multiplies. Such anecdotes are supported by serious psychological studies, one of which showed that men found female geniuses to be unattractive.

Underlying such male fear of smart women is the ideal that men ought to hold the dominant role. The British Master Susan Arkell (now Lalic), who married an even stronger player, Grandmaster Keith Arkell, was asked by her compatriot Cathy Forbes if she wanted to become a stronger player than her husband. Susan responded, “How could a man still be a man after being beaten by hi

s wife?” As outrageous as this quote is, in a way, it goes to the heart of how complex it can be for men to accept powerful women as role models or influences. It is common, on the other hand, for women to identify with the accomplishments of men, as the French feminist Simone de Beauvoir pointed out in The Second Sex. “[T]he adolescent girl wishes at first

to identify with males; when she gives that up, she then seeks to share in their masculinity by having one of them in love with her,” writes de Beauvoir. “Normally she is looking for a man who represents male superiority.”3

My intermingling feelings of envy of and desire for men became clear one Valentine’s Day, which I spent in my apartment with my friend Bonnie. Both of us were single at the time, and our intimate conversation eased the holiday’s shrill celebration of romance and happy couples. We stayed up late discussing relationships and drinking hot chocolate. We realized that we were both attracted most of all to the men who we might like to be. When encountering such a man, I often am cautious, fearing that my own identity and creativity will unravel, replaced by mere admiration for my lover’s brilliance. Realizing all this brings me solace when crushes don’t work out. I know that my desire for some particular man often masks a deeper urge to experience the world in another skin; preferably as a man as I am envious and curious about the more direct way men seem to approach life; ideally a super-talented man, with a high chess rating or fantastic prose style.

“Chess is so heteronormative,” said my friend Martha, upon learning that it is illegal for two Kings to rest on adjacent squares. Although Martha was joking, the sexual symbolism in chess is a rich topic. Chess is an intellectually intimate game in which two players sit for hours, both gazing at each other as well as at the chessboard. The erotic connotations of chessplay were at a peak in Medieval Europe, where Marilyn Yalom, author of Birth of the Chess Queen, points out, “The Queen sent out vibrations that were responsible for sexualizing the playing field.” In a chapter on “Chess and the Cult of Love,” Yalom describes an engraving of a chessgame from a fifteenth-century text: “The chess match was considered sufficient to tell prospective readers that the poems would be about love.” Yalom despondently concludes that today the romantic aspects of chess have mostly faded. There are still remnants of a more sexy chess. At a cocktail party I met a woman who told me she shunned chess as a child, but recently took up the game after she realized that it was a great way to meet guys “who aren’t stupid!” An ironic scene in Austin Powers II: The Spy Who Shagged Me depicts chess as erotica. In it, dopey spy comedian Austin Powers sits down to play chess with a buxom, barely clad opponent. The competition quickly turns to foreplay, with chess pieces used as props.

Chess Bitch: Women in the Ultimate Intellectual Sport

Chess Bitch: Women in the Ultimate Intellectual Sport